Art, Activism, Policy, Power: Colleen Plumb Urban Trees

Colleen Plumb & Urban Tree Canopies

About the artist

Colleen Plumb creates photographs, videos, books, and public video projections about the contradictory relationships people have with other living species. Plumb explores themes of power imbalance and the human appetite for domination of nature.

Plumb’s work has been exhibited around the world, including at the Portland Art Museum, Milwaukee Art Museum, Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, Southeast Museum of Photography in Daytona Beach, and the Notebaert Nature Museum in Chicago, among others.

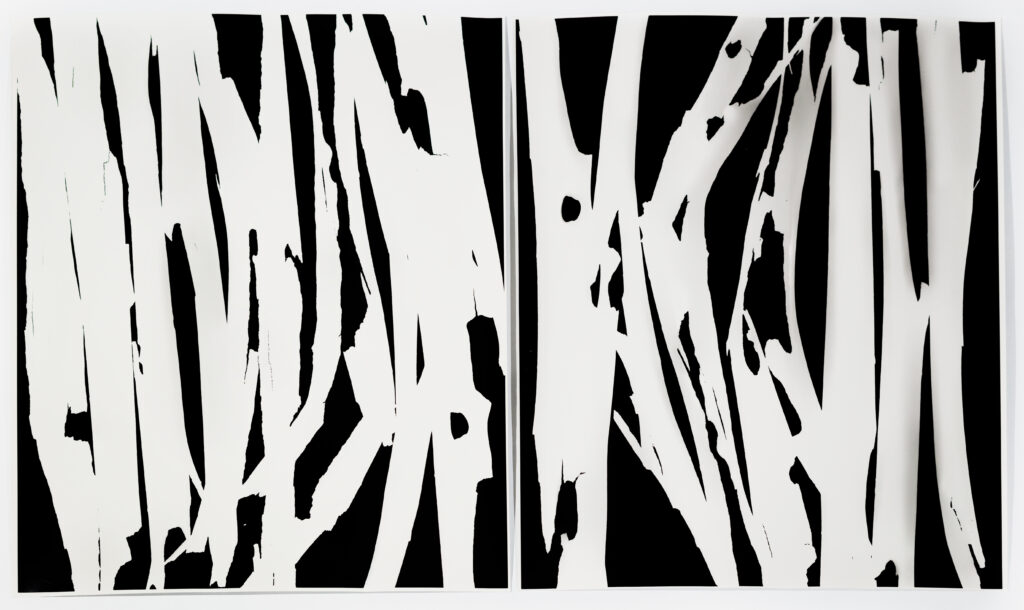

and Burr Oak, 2025, from the series Marrow.

and Elder, 2025, from the series Marrow.

Video: Colleen Plumb on Public Art & Process

About the program

MoCP’s Art, Activism, Policy, Power’s 2025 program welcomes environmental artist activist Colleen Plumb and students from South Shore College Prep and Prosser Career Academy to learn about the importance of trees in combatting climate change and maintaining healthy urban ecologies.

This year’s program is in partnership with Openlands.

Openlands is an organization that protects the natural and open spaces of northeastern Illinois and the surrounding region to ensure cleaner air and water, protect natural habitats and wildlife, and help balance and enrich our lives.

This resource can be adapted to used by educators in any classroom.

Thinking Deeper

Thinking about nature:

What elements of nature do you use or see every day?

Where do you go to experience or be close to nature?

What natural areas in your neighborhood, city, or state have changed during your time living there?

How do you think these natural areas might change in the future?

Thinking about Colleen Plumb’s artwork:

Artist Colleen Plumb’s earlier work is about how humans interact with and or dominate animals. How do you observe people relating to nature at large?

After learning more about Plumb’s practice in public art, how might seeing art in a public space compare to seeing art in a museum?

Learn & Engage

Art

Colleen Plumb shares in her artist statement:

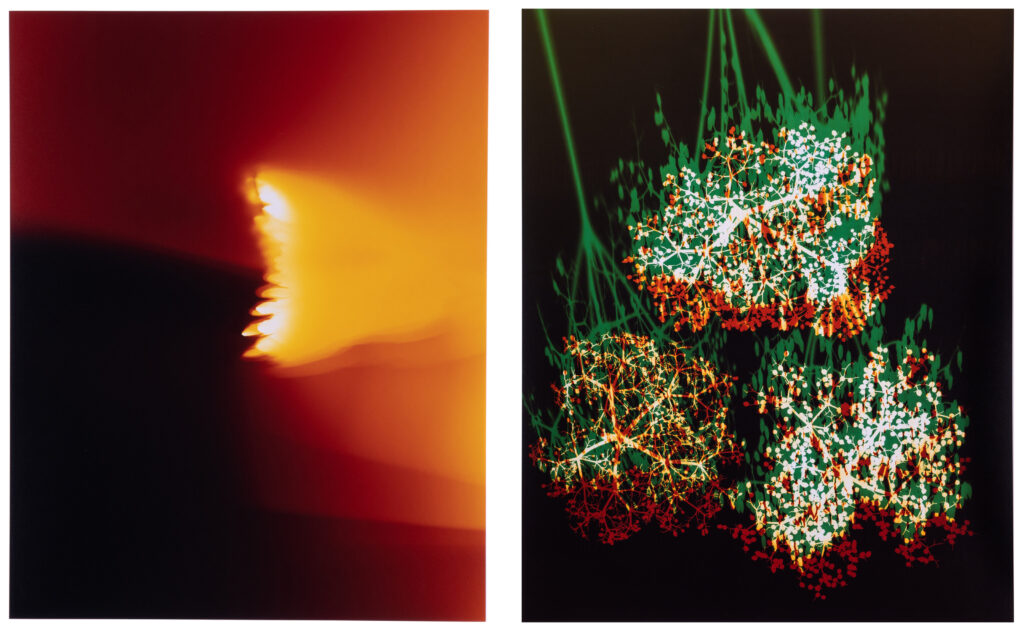

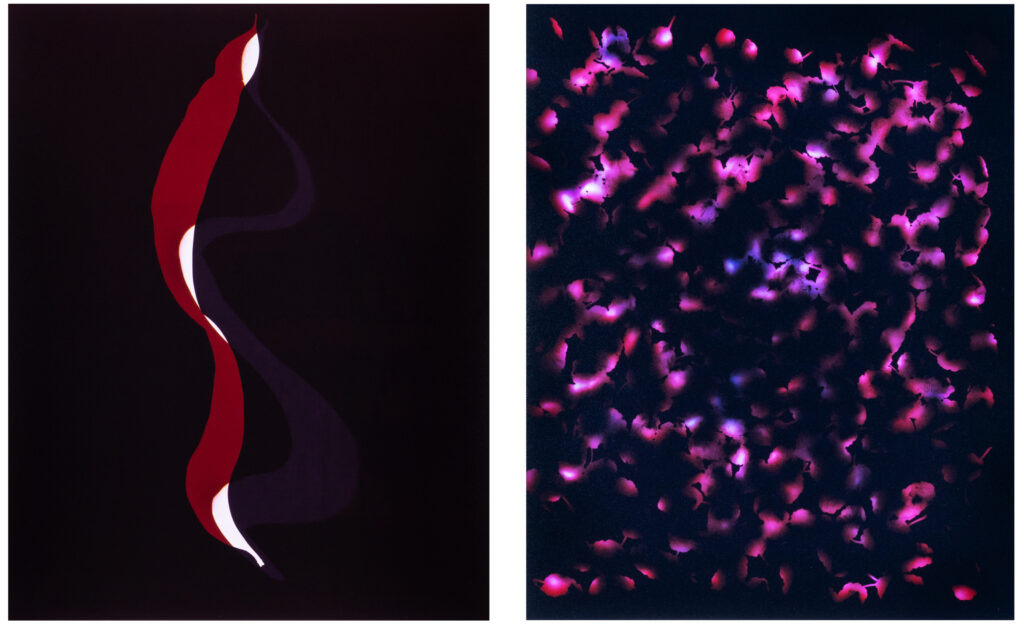

Collecting tree material offered by the forest that exists within Chicago—along sidewalks, parks, and backyards—has become a practice of attention. Through photograms, I consider whether traces of who I regard as “tree-beings” can be translated through light onto paper—whether image can hold their presence. This attempt is less about proof than about opening: a way to see and listen differently. The photogram, as a process that records direct contact, becomes a site where material, light, and time converge—suggesting metaphorical possibilities for reciprocity across species.

The invention of photograms as an early photographic technique paralleled developments in biology and modernism—disciplines that sought new visual forms and ways of understanding the natural world through art and science. My photograms connect with that lineage but belong to this moment. We now know that trees communicate with one another through fungal networks, chemical signals, root systems. This knowledge reshapes how we understand the intelligence, interdependence, and agency of trees, especially now, as ecosystems edge toward collapse. Within this context, my photograms explore the possibility of dialogue—or gestures of kinship and gratitude—toward the urban trees that surround and sustain us.

When I first brought Sycamore bark into the darkroom, the resulting photograms evoked bones and mark-making. In the color darkroom, another ‘voice’ emerged—through hue, shadow, and chance. Using flashlights, gels, and movement, I often relinquish control to see what happens. This process echoes trees’ own relationship to light: responsive, adaptive, necessary for survival. With images made from material from all the vital tree species within Chicago’s canopy, I aim to address the role of urban forests in mitigating climate change and sustaining an environmentally just city.

Activism

What does it mean to be an artist activist?

Activism can take many forms—from marching in protests and boycotts, to withdrawing time and money from organizations that do not align with your values, to simply learning more and raising awareness about the systems of oppression that shape our world, both historically and today.

Artmaking, too, can serve as activism. It may be quiet or loud, depending on how the work is created, shared, or displayed. Consider, for example, the role of art in environmental activism: artists can amplify conversations around healing and care for the planet, using beauty to foster deeper connections between people and nature.

In this session of Art, Activism, Policy, Power, students participate in workshops centered on trees, using them to spark learning, creativity, and care for the Earth, while also reflecting on why this work matters in their own lives.

Policy

Why Are Trees Important in our City and Neighborhoods?

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is a natural and essential component of Earth’s atmosphere, playing a key role in absorbing and radiating heat. However, since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in 1760, CO₂ levels in the atmosphere have increased by 47%, according to the National Forest Foundation. This rise, largely driven by human activity, has caused the average global temperature to increase by 2 degrees Celsius, or approximately 35.6 degrees Fahrenheit. The consequences of this temperature rise are far-reaching: extreme weather events, diminished snow and sea ice cover, intensifying natural disasters, and shifting habitat ranges for both plants and animals.

Trees powerfully combat the challenges posed by increased carbon emissions. Trees absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere and convert it into oxygen, reducing the amount of greenhouse gases in the air. They also prevent soil erosion by absorbing rainwater and provide habitats for countless animals, and provide a wide array of emotional wellness benefits to humans.

As shared by our program partner, Openlands, “Trees are shown to have a positive impact on mental health, and they also increase property values, cool your home in the summer, create oxygen, and clean the air of pollutants.”

Incorporating more trees into urban and suburban landscapes can play a critical role in lowering CO₂ concentrations, mitigating climate change, and improving quality of life for communities.

Tree Reverence and Stewardship

When we plant and take care of existing trees, we help ensure a healthier environment for ourselves and future generations. Teaching artist Colleen Plumb is a TreeKeeper with program partner, Openlands, where she has been trained in urban forestry and certified to care for, protect, and plant trees around the city.

While observing or caring for trees in Chicago, Plumb collects tree specimens (such as leaves, seeds, and bark) to create unique camera-less photograms. The photographs appear as abstract depictions of her reverence for their forms.

Power

In Colleen Plumb’s series, Marrow, she creates photograms as a way to talk about trees.

A photogram is a photograph that does not use a camera to make the image. Instead, objects are placed on top of paper that is sensitive to light. When exposed to light, a photograph is created as light moves around and passes through the objects leaving behind a range of light and shadow.

While photograms were used throughout history around the world, in 1842, Sir John Herschel invented a photographic process called cyanotype or what we commonly understand today as a “blue print” or “sun print”.

In 1843, photographer and botanist Anna Atkins used the cyanotype process to document plant specimens as photograms, using photography for scientific purposes, and publishing the very first photographic book, Photographs of British Algae.

Making a Tree Cyanotype

To make your own cyanotype from tree specimens, you will need:

- Pre-coated cyanotype paper

- A piece of plexiglass or standard window glass

- Cardboard or a hard surface

- Objects you collect responsibly from trees or around trees, such as seeds, leaves, or bark.

- A large container for water

- A flat plastic or glass tray big enough to fit your paper

- And, sunlight!

Directions:

- The paper comes in a black light-tight bag. Before setting up the paper, play with arranging your collected materials considering how each shape will interact with the others.

- Find a sunny location.

- When ready, take out one sheet of paper and quickly arrange your objects on top of it.

- If your objects are flat like leaves, you’ll want to place your plexiglass or glass on top of the items to press them against the paper. If your objects are 3-D like rocks, you should put the glass on the paper first, and your objects on top of the glass.

- Allow your paper to sit in the sun for up to 20 minutes. *If it’s a sunny day, 20 minutes will be enough time. If it is cloudy, add an extra 10 minutes.

- Remove the objects and glass and place your paper in the flat tray.

- Pouring water on top of your paper, you will quickly start to see the blue color get darker. *White areas are where objects blocked the sun, and blue areas are where the sun was shining bright on to the paper.

- Remove the paper from the water and lay flat or hang with clothes pins to dry.

- Dump the water down the sink.

- Look at your new cyanotype and discuss it with friends!

What did you learn about engaging with natural materials while gathering and arranging your cyanotype?