Anticipation

About the Exhibition

Anticipation

Work by:

Susanne Kutter (Germany)

Andrea Bowers (United States)

Karin Müller (Switzerland)

Smith/Stewart (England, Ireland)

Tatterdandelion (Northern Ireland)

Fischli & Weiss (Switzerland)

anet Cardiff & Goerge Bures Miller (Canada)

David Bate (United Kingdom)

Troy Williams (United States)

While approaching her house a woman suddenly drops her groceries and stands frozen in her driveway.

A fully-clothed man lies submerged in a bathtub receiving air only from his partner, who occasionally plunges her head below the water’s surface to deliver him breath from her own mouth and lungs.

Two friends shock each other with electric current, upping the voltage each time.

A young ice skater crouched nervously in position waits for the music signaling the start of her routine to begin.

A man, a woman and a dog stumble up a snowy hill, but never reach the summit to see what lies beyond.

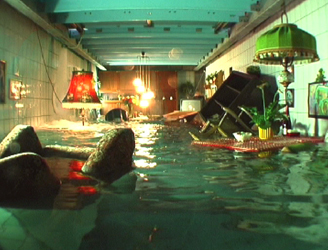

A cozy living room fills up to the ceiling with water.

A man and a woman cover their heads with plastic bags and struggle to remain calm.

As Oscar Wilde wrote in his play The Importance of Being Ernest, “This suspense is terrible. I hope it will last!”

Anticipation, alternately pleasurable and unnerving, is experienced as a potent emotional, and sometimes visceral, charge. A time-based phenomenon, anticipation involves self-awareness and a feeling of foreboding based on the expectation that something is about to happen. Waiting, unsure and expectant, we experience for some time prickly feelings and a state of heightened consciousness that cross-wires psychological and physical sensation.

The experience of anticipation (like all experience) begins with the senses and unfolds in perception, which, as a philosophical question, cannot be divorced from a consideration of the nature of time and space. In “Art as Experience,” John Dewey argues that because man is capable of deliberate expression and excels in the face of complexity, time ceases to be “the endless and uniform flow or the succession of instantaneous points.” Rather, he explains, like space it is the “organizing medium of the rhythmic ebb and flow of expectant impulse, forward and retracted movement, resistance and suspense, with fulfillment and consummation.”1

This idea of time as a continual shifting between anticipation and resolution offers an alternative to the dominant contemporary conception of time as a progressive phenomenon marked by a succession of events, a notion that many philosophers and artists, especially since the emergence of video art in the 1960s, have sought to destabilize.

This conception of time as a linear progression is no doubt reinforced by narrative conventions of literature, cinema, and photography, which typically communicate the passage of time through successive, separate frames of imagery. This hasn’t always been the case. Artists have been grappling with the problem of how to best express time in narrative since Antiquity. During the Archaic period of Greek art, for example, the technique of combining multiple moments of a story into one picture frame predominated.2

From our perspective today, this approach to representation may seem to promote confusing narrative contradictions, however it also hints at the potential for a radically different conception of time altogether. Indeed, instead of pointing to the limitations of the single picture for narrative, it illustrates its possibilities.

Photography is in many ways thought of as the capture of still images from the constantly changing continuum of life. Because we understand (and believe) this, when presented with a photograph, our brain willingly accepts the challenge of filling in the “before” and “after” of the picture. Yet when the image has a durational component, our patience suddenly wears thin. After 100 years of motion pictures as entertainment, and in an age of sound-bites and frenetic internet navigation, we have been trained to expect staccato action and resolution from time-based mediums, if not the ability to move the narrative along ourselves. Yet the effort involved to perceive still and time-based art is in many ways only superficially different. Although still pictures can seemingly be read as a whole in an instant, to really grasp details and comprehend the relationships and content within them we must move our eyes around the image and spend some time thinking. Still photography, like time-based art, is therefore experienced as a spatial phenomenon.

After 100 years of motion pictures as entertainment, and in an age of sound-bites and frenetic internet navigation, we have been trained to expect staccato action and resolution from time-based mediums, if not the ability to move the narrative along ourselves. Yet the effort involved to perceive still and time-based art is in many ways only superficially different.

This exhibition presents the work of nine artists and artist teams who probe the nature of perception by emphasizing the powerful allure of anticipation and suspense in their video and still photography. Rather than concerning themselves with the communication of narrative, these artists are more interested in our psychological response to their work and our experience of the space in which it is presented. Many of them focus on the tension between the moving and the still image, and using devices such as doubling, slowness, repetition, rhythm, and humor, make us acutely aware of the act of looking, often by provoking a visceral response. Many of the artworks they create force us to slow down and confront our need for resolution and distraction, reminding us that “nothing happening” is an impossible condition.

Troy Williams (American, b. 1975) and David Bate (English, b. 1959) make still images that recall cinema. Williams, who is perpetually fascinated by his own obsession with films, makes ambiguous references to the horror films and sci-fi flicks that keep us on the edge of our seat. By reinterpreting the pivotal moments of moments of movies where we are transported from fiction into a state of belief, Williams makes us aware that what we often remember most clearly are the scenes that induce anxiety and fear. Bate works directly in response to Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker in which the protagonists prove to be more fearful of the unknown, better life promised in the “zone” than the familiarity of the life they know. He translates scenes from the film by finding corresponding imagery in Tallinn, Estonia, the city where the film was originally shot and a place that has been experiencing the transition away from Communism over the past fifteen years. As a stalker with a camera, he records as a tourist would the melancholy associated with a society trying to navigate the disconnect between the promise of a better life under Capitalism and the often unfamiliar, disappointing, reality.

Karin Müller (Swiss, b. 1966) also works with cinematic source material in her video The Soloist (2005). Generally interested in exploring the emotional life of men in her artwork, in this case she appropriates scenes from Clint Eastwood movies in which he plays the lonely, mysterious stranger. First isolating moments when his face is seen in close-up and he is waiting, listening, and contemplating his next move, Müller then collages these clips in such a way that there are always two of him on view. As one face glares at and slowly subsumes the other, the soundtrack is also stretched and exaggerated, providing an unsettling accompaniment to this suspenseful, implied confrontation between a man and his psyche.

Like Müller, the artist team of Smith/Stewart (Stephanie Smith: English, b. 1968; Edward Stewart: Irish, b. 1961) investigate emotional and psychological tension. By placing themselves in controlled yet seemingly precarious physical situations, such as covering their heads in plastic or lying at the bottom of a bathtub waiting to be given air, they produce art that is difficult to watch because it taps into our most deep-seated primal anxieties. In both of their pieces on view, suffocation is at once a reality and a metaphor for the perils and comfort of co-dependency in a love relationship.

Similarly, Susanne Kutter (German, b. 1970) plays with themes of security and insecurity in her video of a living room that over the course of an hour floods with water. Particularly resonant after the tsunami and Hurricane Katrina, our experience of the simulated destruction is softened by its slow unfolding in real time and the beauty and grace of the seemingly weightless objects floating in a pool of blue-green. Even after the camera (and our point of view) is completely submerged, the sound remains the same—the violent thrust of water pounding on its own surface—reminding us of the piece’s distressing theme of the anxiety of domestic obliteration.

Sound plays an important role in the work of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller (Canadian, b. 1957; 1960) whose videoHill Climbing (1999) tracks an unseen couple and their dog as they struggle to climb up a snowy hill. The layered, binaural soundtrack is heard through headphones, a device intended to mimic the sensation of experiencing voices and sounds resonating in one’s own head. As the couple stumbles and trudges along, the video loops and they never reach the summit, frustrating our desire to see what is over the horizon and to successfully imagine ourselves located within the image. Similarly,Andrea Bowers’ (American, b. 1964) Waiting (1999) highlights our need to resolve an expectant moment. A simple, elegant video that captures the few seconds before a young ice skater begins her routine, it invites us to empathize with the nervousness and intense self-awareness that accompanies the anticipation of performance.

The nerve-wracking quality of anticipation is sometimes best relieved by humor. One can’t help but flinch when Tatterdandelion (Irish; Nicky Keogh b. 1977; Paddy Bloomer, b. 1976) shock each other with current in their gritty, homespun video Electricy Can Be Fun (2003), and then breathe a sigh of relief and laugh along with them after they survive it. And in the now classic videoThe Way Things Go (1987) by Fischli & Weiss (Swiss; Peter Fischli, b. 1952; David Weiss, b. 1946), a chain reaction of whimsical physics experiments proves that wonder and excitement can be generated by the most unassuming objects, and that to affect us the base thrill of anticipation requires no narrative of human drama whatsoever.

All of these artists, whether employing time-based or still mediums, use aural and/or visual devices that provoke us to critically consider the nature of looking and heighten our awareness of the experience of perception. They do not provide us with closed, resolved stories. Rather by making us wait and sometimes frustrating us, they leave us in a state of indeterminacy and cause us to be aware of the fissure between what we see and what we expect and desire to see. In this process they destabilize the conception of an artwork as a fixed, concrete object full of meaning and reposition it as a durational human experience open to interpretation. Seen from their vantage point, as Nicholas Bourriaud has succinctly observed, “Art is a state of encounter.”3

-Karen Irvine, Curator

1. John Dewey, Art as Experience (New York: The Berkeley Publishing Group, 1934), p. 23

2. Mark D. Stansbury-O’Donnell, Pictorial Narrative in Ancient Greek Art (Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 1-3

3. Nicholas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (France: Les presses du réel, 1998), p. 18

Anticipation has been co-presented with the Goethe-Institut Chicago with assistance from Pro-Helvetia, the Arts Council of Switzerland. The exhibitions, presentations, and related programs of the MoCP are sponsored in part by U.S. Bank; the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency; The Mayer and Morris Kaplan Family Foundation; The Henrietta Lange Burk Fund; The Palmer Foundation; the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs/After School Matters; American Airlines, the official airlines of MoCP, and our members.

The 2006 museum benefit auction Anticipation has been made possible by Oglivy & Mather; US Bank; Ungaretti & Harris;William Blair & Co; Christies; OnRequest Images; and Chicago Social. Additional support has been provided by Boeing; David Grossman & Associates; McCormick Tribune Foundation; Russell Novak & Company, LLP Certified Public Accountants; Smithfield Properties; Stems; StoneArch, Inc., Strategic Selling Advisors; Supreme Frame; Anonymous; David L. Frank; John & Mary Francis Hass; Bill & Vicki Hood; Jack Jaffe & Naomi Stern; Lawrence & Maxine Snider; Margie & Bill Staples; Esther Saks; David Weinberg & Jerry Newton; Sonia & Ted Bloch.

Image Gallery