Work by:

Laurie Anderson

M.W. Burns

Takehito Koganezawa

Jay LeFor

Ann Lislegaard

Christian Marclay

Carsten Nicolai

Gebhard Sengmüller

Gary Simmons

Stenia Vasulka

As a pioneering turntabalist and avant-garde musician, Christian Marclay’s visual artwork is consistently inspired by sound and recording. Marclay is known for altering and lending new context to objects and images related to music, such as exaggerated sculptures of mutated musical instruments. By juxtaposing the concepts of recorded sound with the photograph as visual record, he articulates the differences and parallels that exist between the two forms of documentation. In addition he frequently incorporates themes of abandonment and recovery in relation to the technologies associated with image- and music-making through his recurrent use of aging, found photographs and damaged vinyl recordings. Born in San Rafael, California, Marclay was raised and educated in Geneva, Switzerland. After attending the Ecole Supérieure d’Art Visuel in Switzerland, he moved to Boston and received his BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art (1980). Marclay has had solo exhibitions at venues such as the Fri-Art Centre d’Art Contemporain Kunsthalle, Fribourg, Switzerland; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; Museet for Samtidskunst, Roskilde, Denmark; the Cleveland Center for the Arts; and the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva, among many others. His exhibition record also includes numerous group shows, among them Le Temps, vite! at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Human Gender and Being, Kwangju Biennale, Korea; Sonic Boom: The Art of Sound, Hayward Gallery, London; Videodrome, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York; and the Venice Biennale (1995, 1999). Christian Marclay lives and works in New York.

Steina Vasulka has been a pioneer in video art ever since the emergence of the in the late 1960s. Trained as a classical violinist, Vasulka creates work that is deeply invested in sound, specifically its relationship to moving images. Through the use of complex electronic imaging tools, Vasulka has been able to explore the relationship of sound to image from a variety of angles; creating pieces in which the audio is controlled by the visual, the visual is controlled by the audio, or both are controlled by an outside source. In her continual investigation of the electronic nature of video signals, Vasulka morphs image and sound recordings to create unsettling hybrids. Born in Reykjavik in 1940, Vasulka studied violin and music theory at the Music Conservatory in Prague from 1959 to 1963, where she met her husband, Woody Vasulka. The couple moved to the United States in 1965, and in 1971 founded The Kitchen, a major center for alternative media arts in New York. The couple’s collaborative works have been exhibited internationally and have won many awards; Steina’s independent work has been shown in venues such as Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; The Kitchen, New York; Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; The Whitney Biennial, New York; and Mass MOCA, North Adams, Massachusetts; among many others. Vasulka lives and works in Santa Fe.

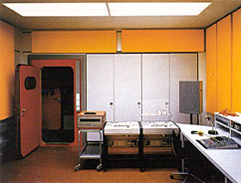

Gebhard Sengmüller is a member of the artistic group “vergessen©,” (“forgetting”), a collection of artists who create “artistic and scientific” projects in an exploration of the phenomenon of forgetting. In their performances, exhibitions, presentations, screenings, and discussions, the group attempts to draw attention to the inevitability and persistence of forgetting and its link to time. “Space only exists as memory. Images, sounds and fragrances are constantly overlapped by new images, sounds and fragrances,” the group explains. Sengmüller’s contribution to the ongoing project was to visit ORF (Austrian Broadcasting Corporation) studios and photograph the large electromagnets used to instantly erase audio and video tapes. Sengmüller has been included in many exhibitions including S.O.S.: Scenes of Sound, Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York; Lowtech, Shedhalle, Zurich; Postmasters Gallery, New York; Forum des Images, Paris; Lost in Sound, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Deaf Fesitval, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; and the European Media Art Festival, Osnabrück, Germany. Sengmüller studied at the academy of music in Vienna and is currently a MFA candidate in visual media design at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna.

“One of my jobs as an artist is to make contact with the audience, and it has to be immediate,” says Laurie Anderson. One of the world’s most acclaimed performance artists, Anderson has been creating multimedia productions and artworks for thirty years. Starting in alternative venues in the early 1970s, Anderson gained recognition for her multidisciplinary approach to “live art” by challenging traditional conventions and creating torrents of imagery, light, spoken words, music, and sound. Throughout her multifaceted career, she has written numerous songs and musical scores for film, dance, and orchestra; performed at music festivals and venues throughout the world; presented public lectures; and created a variety of installations and artworks using mediums such as photography, lithography, words, music, and sculpture. Anderson received her BA in art history from Barnard College (1969), and her MFA in sculpture from Columbia University (1972). Selected performances include Songs and Stories from Moby Dick (1999); Civil Wars by Philip Glass and Robert Wilson (1997); The Speed of Darkness (1997); The Nerve Bible (1995); Voices from Beyond (1991); and United States (1983), all of which have toured internationally. Selected solo exhibitions and installations include Laurie Anderson’s Anthology, Museum of Contemporary Art, Roskilde, Denmark; Musée d’Art Contemporain, Lyon, France; Dal Vivo (Life), Fondazione Prada, Milan; Guggenheim Museum SoHo, New York; Laurie Anderson: Works from 1969 to 1983, Insitute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; and Laurie Anderson: Artworks, Institute of Contemporary Art, London. Born in Chicago, Anderson lives and works in New York.

Takehito Koganezawa creates video installations that combine visual and audio recordings to construct and conflate past and present, time and place. His use of repetition and random sequencing of imagery and sound patterns creates a nonlinear narrative open to a variety of interpretations. The discordant nature of the work both illustrates and frustrates our need to reconcile image and sound in order to make sense of a given environment. Koganezawa frequently collaborates with sound artists and musicians, such as Carsten Nicolai, to add another chance element to his work, allowing his visual imagery to be affected by pairing with another author’s sound compositions. Koganezawa received a scholarship from the Pola Foundation, Tokyo after graduating from Musashino Art University, Tokyo (1998). His solo exhibitions include shows at Wohnmaschine, Berlin; Project Rooms, ARCO, Madrid; Media City Seoul 2000; and Rhodes + Mann, London. He has been included in a variety of group exhibitions, including Translated Acts, Queens Museum, New York and City Vision: City Clips, International Film Festival, Rotterdam. Presently living in Berlin, Koganezawa was born and raised in Tokyo.

Jay LeFor creates artworks that combine photography and sculpture to probe the internal workings of the human body and the physical qualities of sound. By recording his brainwaves and transmitting the resulting sound through fluid, LeFor translates the inner workings of his mind into audible and visual data. His illustrations of sound waves are reminiscent of scientific experiments; they hint at the potential to measure human thought and emotion. Currently living and working in Chicago, LeFor is a recent graduate of the graduate school of fine arts at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, where he received numerous scholarships and awards, including Best of Show, MFA Thesis Exhibition (2000). He has had solo exhibitions at the Snite Museum of Art and the ISIS Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Indiana; and The Rourke Art Gallery, Moorhead, Minnesota. LeFor has also been included in numerous group shows such as Under the Influence, Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago; ARCGallery, Chicago; The 40th Annual Midwestern Art Exhibition, Nocoadoches, Texas; Intonations, A.R.C. Gallery, Chicago; and No Big Heads, Anchorage, Alaska.

Seeing Sounds, Hearing Images

By Christoph Cox

I

“This is not a pipe” (Ce n’est pas une pipe) René Magritte famously inscribed across his otherwise ordinary painting of a pipe. No mere visual one-liner, Magrittés gesture draws attention to the three heterogeneous domains-thing, image, and word-that come into conjunction on his canvas, and highlights basic issues of representation that have always attended the visual and verbal arts: what is the relationship between images and things, words and things, words and images?

With a nod to Magritte, Christian Marclay’s The Sound of Silence (1988) is a photograph of a Simon and Garfunkel record. In the photograph, the record’s label bears the (silent) written title “The Sounds of Silence,” a reference to the song’s paradoxical chorus, in which the duo sing of how silence might sound. Simon and Garfunkel’s title is the title of a song and of a recording of the song. Marclay’s title is the title of a photograph of a record. Song, record, photograph: is Marclay’s image merely a representation of a representation? Not at all. For his silent photograph of a silent object finally captures the elusive sonic silence that confounded the singers and the song in the first place.

Magritte’s questions about representation-about things, images, and written words-remain within the realm of the visual. Marclay’s photograph takes us a step further. It carries us into the realm of the audible and, hence, pushes us to inquire about broader and deeper connections and divisions in the modes of our experience: What is the image of a sound? What is the sound of an image? What is the relationship between the visual and the audible, between seeing and hearing?

II

We are endowed with five senses: five modes, proximal to one another, yet stubbornly discrete, each with its own objects and qualities. Throughout modern history, however, artists and scientists have attempted to overcome this segregation of experience, to bridge the apparently unbridgeable gaps between seeing, hearing, tasting, touching, and smelling.

In 1786 Ernst Chladni, the father of modern acoustics, dragged a violin bow across the edge of a metal plate covered with sand. Rumbling this way and that, the sand began to fall into distinct figures, from simple lines and curves to elaborate patterns reminiscent of stars, labyrinths, and topographical maps. Chladni believed he had discovered something extraordinary: the image of sound, a direct line of connection between the two most aesthetic of senses: seeing and hearing. Gazing in astonishment at the patterns he had generated, he is said to have declared: “The sound is painting!”

Chladni’s experiments have become the stuff of high school physics. Yet they have also inspired a number of contemporary artists. Notable among these is the scientist, painter, and musician Hans Jenny, whose photographs and videotapes of vibrating plates captured the psychedelic Zeitgeist of the late 1960s, and in the decades since, have inspired New Agers and Techno heads alike.

A century before Chladni, the philosopher John Locke reported his bewilderment at the case of “a studious blind man” who experienced the color scarlet as the sound of a trumpet. “Synaesthesia,” as this peculiar phenomenon of sensory crossover is called, is presumably as old as humankind; yet only within the past two centuries has it come to prominence among scientists and artists. The poet Charles Baudelaire wrote of a “blending” and “correspondence” between “sounds, scents, and colors.” The writer Vladimir Nabokov noted that, for him, certain vowel sounds evoked very particular hues. The painter David Hockney claims to have produced sets for the Metropolitan Opera simply by hearing the music as colors and shapes. And the composer Olivier Messaien told an interviewer: “I have a gift-it’s not my fault, it’s just how I am-whenever I hear music, or even if I read music, I see colors.”

In his new book on the subject, research psychologist John Harrison pauses to ask: “When is synaesthesia not synaesthesia?” His answer: “When it is a metaphor.” Here science and art part ways. In their efforts to locate synaesthesia in the physical stuff of the brain rather than the imaginations of artists and audiences, scientists such as Harrison miss what has always been aesthetically intriguing about synaesthesia-in a word, metaphor. Etymologically, “metaphor” means “to carry across,” to transfer something from one sphere into some other domain foreign to it. Sound into sight. Sight into sound. It is this kind of imaginative transfer that guided Wassily Kandinsky, who hoped that his abstract canvases caused the viewer to hear sounds, and inspired Earle Brown and Cornelius Cardew, whose “graphic scores” consist entirely of shapes and figures for performers to translate into sounds. Today electronic music producers such as Tetsu Inoue and Mixmaster Morris supplement their own aesthetic faculties with MetaSynth, a synaesthetic software program that translates sounds into images and vice versa. Such crossovers always highlight both the similarity and the difference between the two phenomena and their spheres; the translation of the one into the other and that which resists this translation; a threshold crossed in the imagination that nevertheless remains elusive and transient.

III

The literal, the true, and the obvious, remarked Friedrich Nietzsche, are merely “metaphors that have become worn out … drained of sensuous force.” The role of art, he insisted, is to remind us of the metaphorical transfers that ground all of human experience and creativity. After a half-century of sound cinema and television, and two decades of MTV, the conjunction of “the audio” and “the visual” has become banal. The work included in “Audible Imagery” pauses the daily torrent of audio-visual information in order to restore the wonder and strangeness of sound, of image, and of the relationships between them. In so many ways, the work presented here asks us to substitute the metaphorical for the literal, imagination for reflex and habit. In the process, it prompts us to ask what seeing is, what hearing is, and what it might mean to hear images and to see sounds.

Out on the sidewalk, M.W. Burns’s Posing Phrases (2001) offers a hilarious and alarming, literal and metaphorical take on “the sound of photography.” The piece draws solely from the verbal ejaculations of the fashion photographer, a staple of our cultural imagination ever since David Hemmings’s performance in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966). Exploiting sound’s capacity to be detached from image and context, the piece transforms the dictatorial commands of the photographer into a disembodied sonic superego that, from nowhere, barks orders at passers-by.

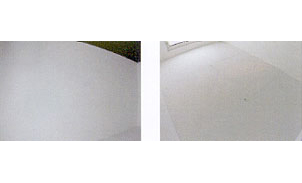

Carsten Nicolai and Jay LeFor take up Chladni’s and Jenny’s suggestion that the bridge between sound and sight is made of waves. The luscious mounds and ripples that glisten in Nicolai’s Milch (2000) photographs are, literally and figuratively, made of sound. And the metallic undulations of LeFor’s Electronics of Mind (2000) remind us that our own gray matter hums and throbs like-and with-waves of sound.

Unlike film or video, traditional photography is a generally still and silent medium. Indeed the video pieces included here seem to aspire to the condition of still photography: to slow the flow and to denaturalize the relationship between sound and image. Video art pioneer Steina Vasulka’s Trevor (1999) takes that most ordinary of phenomena, human speech, and transforms it into an abstract audio-visual choreography. The human face becomes pure matter-all flesh, bone, and muscle-and electronic signal-a mass of melting pixels. No longer the bearer of transparent meaning, speech becomes pure audio. If the piece separates voice and face at one level, it reunites them at another. Exploring the synaesthetic possibilities of the digital medium, Vasulka has constructed the piece so that sound controls image, allowing her subject¹s voice to modulate the speed of the video clips.

Takehito Koganezawa and Carsten Nicolai’s collaboration On the Way to the Peak of Normal II (2000) accomplishes a similar abstraction, deceleration, and unhinging of sound and image. The piece presents an extraordinarily reduced collection of images and sounds, brief snippets that follow one another like blinks of the eye (and ear). Shot in a white, all-but-empty chamber, Koganezawa’s video image is stripped down to its formal rudiments: light, angle, color, texture, focus, and movement. Nicolai offers a similarly spare and abstract collection of electronic sounds: Geiger-counter crackle, throbbing pulses, and mechanical hum. Shuffling randomly, the image- and sound-files function independently of one another and bear equal weight, calling our attention to each fleeting conjunction in the enormous cache of possible permutations. Without beginning or end, the piece encourages us to inhabit, rather than merely to observe, its audio-visual space.

Complementing Koganezawa and Nicolai’s piece, Ann Lislegaard’s In Another Room (2000) presents a cinema of pure light and sound. Visually the piece recalls the early Minimalist flicker films of Paul Sharits, Tony Conrad, and Arnold Dreyblatt. Yet here sight is subordinate to sound. Reducing the image to a sound-activated strobe cast on a white wall, the piece is driven by a fragmented female voice-over and the mismatched audible movements of her male protagonist. Constantly cut, layered, repeated, revised, and panned from side to side, the vocal track draws attention to the very process of audio recording and explores sound’s capacity for layering and temporal-spatial dislocation. The narrator’s voice is calm and deliberate, yet the edited composite is obsessional and, at times, frantic and contradictory. Throughout the piece our visual imaginations struggle to catch up with, and to sort out, the elusive auditory descriptions and events.

Marclay’s Chorus I (1988) richly resonates with Lislegaard’s vocal exhibition. Mouths without voices, images without sound, Chorus I is a kind of visual inversion of Lislegaard’s imageless voice-over. Yet both pieces work on the senses in similar ways. Like Lislegaard’s, Marclay’s “voices” seem at odds with one another. Turned this direction and that, and clearly cut from miscellaneous contexts, these mouths seem to sing rather different songs. Perhaps they are laughing, screaming, or shouting. In any case, these “voices” are a motley bunch whose collective sound, one imagines, is cacophonous. While, taken together, they form a visual unity (or “chorus”), the multiplicity, heterogeneity, and fragmentary nature of this collection prevents one from grasping the whole and instead leads the eye from one image to the next. As such, the piece takes on the temporal quality of a musical composition, recalling the audio cut-ups for which Marclay is best known.

Like The Sound of Silence, Chorus I presents an audio-visual metaphor and a provocation to synaesthetic experience. Silent images that capture moments of lost or absent sound, these photographs enjoin the imagination to fill in the missing sonic register. Marclay’s White Noise (1993) presents another kind of metaphor, at once more abstract and more direct. Covering a wall from top to bottom, an array of found photographs is pinned face down. The individual elements are all variations on a rectangular theme, of various sizes, in various shades of white, and variously curled, bowed, or bent. Taken together, they form a textured monochrome, a dense and variegated mass of images without any evident content. A perfect visual analogue to the sonic phenomenon of “white noise,” Marclay’s piece examines that wonderfully synaesthetic phrase, transposing the visual and the sonic, the metaphorical and the literal.

Marclay’s work with found photographs and found sound often explores the themes of absence and loss that always haunt the recorded object. These themes are also taken up by Gary Simmons in his wistful web project Wake (2000). While a male and a female voice hum ballads from a bygone era, the movements of the participant’s hand conjure up partial and evanescent photographs of empty ballrooms and dancehalls. Both sound and image register a host of absences (absent events, songs, places, people), and each tries to supplement the other. Elegantly modeling human memory, the piece captures the way in which our remembrance of things past lives on as a mutually evocative association of sounds and images that, with effort, can be called forth from the recesses of memory only to recede again of their own accord.

“I wanted to make songs that were more like remembering than listening,” remarks Laurie Anderson, describing her now-classic sound-art installation Handphone Table (Remembering Sound) (1978). Simmons’s piece projects the private contents of memory onto the public space of the screen. Anderson’s installation reverses this movement. For the onlooker the piece is silent and obscure. Yet for the participant it is powerfully audible and immediately compelling. Completing the electrical circuit, the participant’s body serves as an amplifier that fills the head with sound. Between onlooker and participant, a photograph bridges the gap, offering visual instructions for this sonic experience.

Photographs and recordings may stem the tide of forgetting and preserve the passing moment; yet they are equally subject to erasure and loss. Gebhard Sengmüller’s Erasure Coils series (1998) presents a kind of technological analogue to human forgetting: the electromagnetic bulk eraser employed by broadcasting companies to delete video tapes. Far from mourning the loss of sights and sounds, Sengmüller’s sober photographs seem wryly to celebrate these black holes of audio-visual information that promise relief from the bureaucratic clutter surrounding them and from the information overload to which their owners contribute. Sengmüller’s series forms part of a larger collective project (Vergessen.com) to affirm forgetting as a necessary but neglected feature of human and technological memory. Self-effacing in more ways than one, Sengmüller’s documents imagine, in their very content, their own consumption and erasure as images.

Resonating with Marclay and Sengmüller’s, Nicolai’s ongoing experiment Realistic (1998) also plays with the relationships between recording and erasure, audible and visual noise. Cycling through a tape recorder without an erase head, a tape loop continually registers the sounds of the exhibition space. Ambient sounds pile on top of one another, gradually producing a thick slab of white noise. Or so one supposes; for the piece itself-notwithstanding the quiet flutter of the apparatus-is silent. In place of audible noise or random sound, we are offered an array of visual and conceptual representations: tape loops recorded at previous exhibitions, Polaroids of randomly piled tape, and a scientific diagram showing how self-replicating networks produce errors and mutations. Circulating among these elements, we gradually approach that zone of indeterminacy where the audible and the visual, the sensible and the conceptual, the repetitive and the random blend and correspond. So many metaphors and synaesthetic moments, so many connections and disconnections, “Audible Imagery” rewires our imaginations. Disjoining habitual connections, it opens up new pathways and bridges, allowing new leaps and transferences between hearing and seeing, sound.