Manufactured Self

About the Exhibition

Manufactured Self

Work by:

Philip Kwame Apagya

Tina Barney

Walead Beshty

Shannon Ebner

Jung Yeondoo

Nikki S. Lee

Alex MacLean

Peter Menzel

Martin Parr

Meridel Rubenstein

Tomoko Sawada

Orit Siman-Tov

Brian Ulrich

Consumption increasingly appears central to the construction of collective and individual identity in the contemporary world. Manufactured Self looks through the critical lenses of thirteen international artists to explore how the things we consume both reflect and construct our identities, how we’re manipulated by clever marketers, and how we’re occasionally satisfied by what we consume. It is appropriate, even ironic, that these artists have chosen photography as their mode of exploration. For most of the past 100 years photography has been the primary vehicle for promoting and selling the very self-defining goods they are talking about.

The things we buy reflect our tastes and social status. But they can also simulate taste and help us feign social status. Martin Parr’s (United Kingdom, b. 1952) series, Sign of the Times: A Portrait of the Nation’s Tastes captures this phenomenon effectively. Parr was part of a production team headed by Nicholas Barker of the BBC that interviewed homeowners and photographed nearly 2000 British houses in the early 1990s. The people were asked about their choices of home decoration. The project addressed questions of national taste by documenting the way the English have identified what they like, and the image they hope to project with regard to their homes. Parr’s resulting pictures, with accompanying quotes from interviewees, record a particularly British sense of social order, akin to the American notion of “Keeping up with the Joneses.” The owners of one home, depicted by a portrait of a Labrador sitting near the classical white fireplace with a gold electric fire insert state, “I think we are looking for a look that is established, warm, comfortable, traditional.” In another image, of three porcelain objects neatly placed on a window sill with a pink valance and flowery curtains, the owners state, “It’s this Edwardian look that we’re trying to achieve from the bottom right up to the top of the house.”

We feel or have been convinced that we are a reflection of what we own, but we are not always seen by others as we see ourselves. As Nicholas Barker sums up after his research, “All social classes, my own included, display a certain absurdity in their efforts to distinguish themselves from each other…Most people, it seems, define their taste in opposition to the tastes of others and find it easier to talk about what is wrong with other people’s choices rather than what is right about their own. Particularly noteworthy is the way people are quickest to distance themselves from tastes which are both similar to their own and held by others with whom they are competing in some respects.”

Sharing many of Parr’s concerns, Jung Yeondoo (Korea, b. 1969) photographed 34 middle-class families in their living rooms in Evergreen Tower, a typical apartment building in Seoul. The architectural plan of each living room is identical, including four fluorescent light fixtures on the ceiling. Jung documented each family from the same camera angle to emphasize the standardization and “Westernization” of each living space. The only difference is how the families are posed, and their selection of furniture and décor, emphasizing the uniqueness—or, more relevantly, the lack thereof—of each family. His photographs suggest that, where one finds rapid social mobility, one often finds a corresponding increase in anxiety about personal tastes, and the need to conform to the trappings of a particular social status.

With rising personal wealth, consumption increasingly involves an appropriation of goods that goes far beyond the satisfaction of “needs” which might reasonably be regarded as basic, i.e. such as food, clothes, and shelter. In parts of the world where a large percentage of the population is well off, consumers are motivated by sometimes abstract “needs,” such as to communicate particular values or ideals, or to orient themselves socio-economically. Commercial photographer Peter Menzel (United States, 1948) offers a lucid illustration of the global economic disparity of real vs. abstract needs in photographs of the homes and possessions of families around the globe, each representing the median income of their country. From South Africa to Mongolia to Japan to Iceland, the subjects place all of their household belongings in front of their dwelling for unique family portraits that, viewed in relation to each other, emphasize the cultural and economic underpinnings of perceived needs.

Jung Yeondoo’s series entitled Bewitched—derived from the popular television sitcom—displays two portraits of the same person in a dual slide presentation. One side conveys his or her present circumstances; the other his or her aspirations or fantasies. Jung interviews his subjects about their visions of their futures and then visualizes their dreams in a photograph. A young woman mopping the floor at a Baskin Robbins ice cream shop imagines her mop as a spear and dreams of being a polar explorer; a young man who works at a gas station dreams of being a Formula 1 race car driver. Taken in many different countries, these portraits not only communicate personal wishes, but also reflect widely varying socioeconomic situations in each country. For example, in rapidly industrializing China, the subjects speak ambitiously about their futures. A young bicycle deliveryman dreams of becoming a successful storekeeper; a karaoke bar waitress aspires to become a pop star. By contrast, in Japan, many subjects appear overcome by a sense of futility after a long period of postwar modernization and more recent economic boom and bust. This is reflected, for example, in a photograph of a man who seeks spiritual fulfillment by aspiring to be an art teacher, while in reality he is a successful businessman working in the advertising industry.

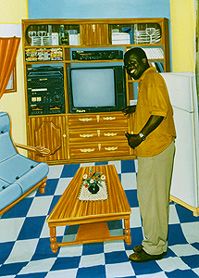

African artist Philip Kwame Apagya’s (Ghana, b. 1958) casual studio portraits of Ghanians posed in front of a variety of painted backgrounds reflect the aspirations of his clients: boarding a private plane, standing in front of a suburban dream house, pointing to a new television. This approach is rooted in a tradition of West African studio portraiture in which the subjects often choose to be represented differently than they actually are by wearing clothes provided by the photographer or incorporating props that symbolize membership to a different socioeconomic group. Apagya’s subjects have been seduced by an affluent fantasy world that reflects current trends and popular fads out of their reach.

Tina Barney’s (United States, b. 1945) portraits of affluent people in the United States and Europe, infused with a sense of entitlement and privilege, deliver a detailed rendering of the trappings of wealth. These people are born into an identity acquired and manipulated by their ancestors, that, to a certain degree, they are forced to accept. While seeking out the familiarities of aristocracy—Barney was born into a wealthy American family—she documents her subjects in their typically elaborate environments and suggests that inherited wealth does not necessarily make for a carefree, uncomplicated life.

Nikki S. Lee (South Korea, b. 1970; United States resident) physically transforms herself to fit in with specific social groups that fascinate her. She seems to imply that we can choose our social group consciously rather than being born into it. From punk to yuppie, rural white American to urban Hispanic, lesbian to tourist, Lee’s characters traverse age, lifestyle, and culture. Part sociologist and part performance artist, Lee infiltrates these groups so convincingly that in individual photographs it is difficult to distinguish her from the crowd. However, when photographs from the projects are grouped together it is Lee’s own Korean ethnicity, drawn like a thread through each scenario, that reveals her subtle ruse. Lee believes that “essentially life itself is a performance. When we change our clothes to alter our appearance, the real act is the transformation of our way of expression—the outward expression of our psyche.”

Tomoko Sawada (Japan, b. 1977) makes a similar statement using the standard format of professional studio portraits used for arranged marriages in Japan. Offering herself as thirty different possible candidates for matrimony, Sawada explores how she could be defined and judged by other people. Dressed variously in kimono, professional clothing, and more edgy attire, Sawada’s transformation from picture to picture is astonishing. Like Lee’s performance, the importance of even the slightest shift in how she lays her hands on her lap or the tilt of her chin are social indicators that can be read and understood by a range of cultures.

The social construction of need—and marketers’ roles in shaping it—is perhaps most apparent in goods designed to express lifestyle. In a world strongly influenced by the North American middle class since the Second World War, the shoes and clothes one wears, or where one shops for groceries, can be major components of defining identity. Whether one belongs to the mainstream or its counterculture, chances are industry has the right product for your idea of yourself. Without irony, consumers appropriate the accessories of even supposedly “alternative” lifestyles, not considering the manufactured identity those products are designed to conjure. Meridel Rubenstein’s (United States, b. 1948) portraits of “Lowriders” in northern New Mexico provide a good example. Emerging in the 1950s and 60s, the lowriders’ highly stylized cars adorned with small murals, messages, and religious marks became a powerful symbol of pride and individuality, and an icon for Chicano defiance against mainstream American culture. By the late 1970s tricked-out cars and aftermarket auto accessories were a cottage industry and today it is a multibillion-dollar business.

Alex MacLean’s (United States, b. 1947) aerial views of housing in America effectively survey where and how Americans choose to live, and make a statement about both individual and collective values. Foremost among MacLean’s observations of urban and suburban housing developments is the tremendous lack of diversity with respect to design and architecture. Economic, regulatory, and commercial trends conspire to make new housing homogeneous and undifferentiated from one part of the country to the next. Retailers such as The Home Depot, which opens a new store every forty-eight hours in the United States, assist substantially in this standardization process. Some, like IKEA, circumvent the need to imagine personalized interiors by displaying fully furnished model rooms that consumers can acquire whole. While consumers of course have freedom of choice, these retail practices and their outcomes push us to consider the extent to which individual tastes are, in fact, not all that individual.

The success of advertising can be measured by the extent to which consumers rely on the mass media in organizing their own identities. The fact that consumers oftentimes feel their individual tastes are unique must be regarded as a remarkable triumph of corporate “target-marketing.” Brian Ulrich (United States, b. 1971) documents the everyday activities of consumption and explores the roles we play as targets of marketing and advertising. Ulrich’s pictures document people in a cathartic state of consumption, usually oblivious to the photographer. In one image a man holds a fishing pole in the sports section of a department store and appears to be entranced with the idea of fishing—the product and designed environment have already initiated his escape from his everyday life. In another image a women clutches a wedding dress amongst dozens of choices, seemingly coerced into believing that the dress she chooses is going to have a significant effect on the happiness of her marriage. It is the goal of the marketers to invent particular lifestyles that individuals tend to incorporate into their view of their ultimate happiness.

Perhaps extending Ulrich’s depiction of absorbed consumers, Walead Beshty (United Kingdom, b. 1977) investigates the physical space of shopping in The Phenomenology of Shopping. Dressed in a t-shirt and jeans he photographs himself as a bizarre version of the all-American consumer with his head completely inserted into merchandise and store displays in malls around the country. By hiding his face—the one solid clue to his individuality—in the product, and having his body go completely limp, Beshty loses all the functions of an active consumer, offering an absurd reflection on and extension of the meaning of “consumption.”

In post-industrial societies, consumption increasingly involves services and experiences, not physical goods. Orit Siman-Tov (Israel, b. 1971) explores contemporary Israeli life as seen through public leisure sites and their inhabitants, and reflects an influence of standardized Western lifestyle. Each of these sites is stripped of its cultural and natural landscape and designed for a universal feel. However, in each of Siman-Tov’s pictures, there are traces of Israel, particularly around the edges of the frame: people lounging by a pool in the desert, skiing on Israel’s only ski resort at Mt. Hermon, or attending an exercise class. There is an added tension in these images, however, in that the safe, relaxing activities they portray contrast with the daily news seen in the West of armed conflict and political strife.

Finally, another effect of consumer culture is the isolation of the individual from real social and political change and events. When abstract concepts like “leisure” and “lifestyle” are made concrete in order to sell products that homogenize people into marketers’ target groups, the concrete realities of war, vast cultural change and political unrest become distant and abstract. Shannon Ebner (American, b. 1971) offers a striking response to this phenomena in her series of images depicting isolated people walking through Los Angles with a letter on his or her shirt. When the images are hung side by side, they spell “SELFIGNITE.” Clearly referencing events in the Middle East, and the “War on Terror,” this project could, among other things, address the futility with which individuals seeks to establish their individuality amidst the marketing and media blitz.

-Natasha Egan, Associate Director

This exhibition and related programs are sponsored in part by OnRequest Images, the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency;Mayer & Morris Kaplan Family Foundation; the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs/Gallery 37; LG electronics, Chicago and American Airlines, the official airlines of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, and our members.

Image Gallery