Mary Ellen Mark: Twins and Falkland Road

About the Exhibition

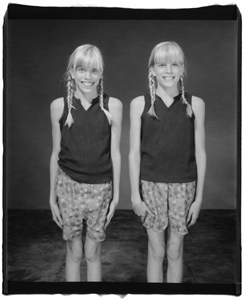

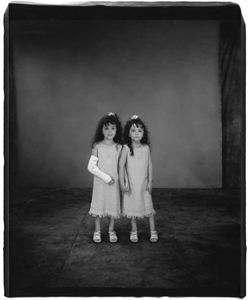

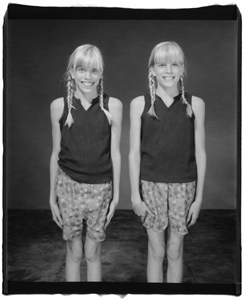

Mary Ellen Mark, Twins, 2001, 2002

Mary Ellen Mark is one of very few contemporary photographers who manage to work in the realms of art, social documentary and photo-journalism without compromising the integrity of any of them or herself. For the past 35 years, in 14 books, and hundreds of media publications she has recorded prostitutes, rodeos, circuses, street children, mental health facilities, film production—the list is long and varied. Knowing full well that photographing people who are radically different than the photographer can turn exploitive, she has developed a reputation for humanitarian concern. As she says, “In most cases, if I didn’t tell their story, nobody would.” She is, in fact, seriously interested in ‘their stories’ and uses photography as an instrument for expanding our understanding of her concerns, not an exclusive formal end in itself. The socially responsible photographer has exactly the same task with subject as with audience: to engage without offending and to communicate completely without becoming neutral.

The Twins project is the result of four years of visits to the Twins Days Festival in Twinsburg, Ohio. During 2001 and 2002, Mark used the Polaroid 20×24 camera in a large tent studio on the grounds of the festival. This involved driving a caravan of three trucks full of gear and a crew of twelve from New York to Ohio. Martin Bell’s filmed interviews with the subjects of the photographs are an integral part of the whole project, as are Mark’s telephone interviews, fragments of which turn up in the text of the accompanying Aperture book. But visible in the pictures, through all this technical dexterity and documentary circumspection—Mark is a working professional photographer, it should be remembered—is her compassion. In the faces and the words there is ample evidence of a very human transaction. Mary Ellen has a long history of bringing the camera together with people who are generally treated as oddities and outsiders in order to help those who consider themselves insiders to understand them—and perhaps themselves.

Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay

Twins and Falkland Road bracket Mary Ellen Mark’s career. The earlier project in India, 1968 to 1981, also depended heavily on compassion and repeated attempts to establish trust, but in this instance across wide cultural and social barriers. The pictures themselves are less rigorously formal than Mark’s later work, which perhaps reflects more the difficulty and cramped quarters of their making than aesthetic choice.

The lengthy introduction to the 1981 book on this project serves to contextualize the photographs for the viewer and perhaps also to prevent simple moral condemnation and dismissal. It is a diaristic text reflecting both Mark’s personal feelings about this exploitive and dangerous world and her research into a culture other than her own. Like her predecessors Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange, Danny Lyon and Eugene Smith, Mark is suspicious of photography’s ability to communicate without deception by itself—hence the need for textual support.

An excerpt from Falkland Road, written by Mary Ellen Mark:

“I thought about Falkland Road for ten years. I had gone there in 1968 on my first trip to India. I went back on each of my succeeding trips.

Falkland Road is lined with old wooden buildings. On the ground floor there are cage-like structures with girls inside them. Above these cages the buildings rise three or four stories, and at every window there are more girls—combing their hair, sitting in clusters on the windowsills, beckoning to potential customers. They vary in age from eleven-year-old prostitutes to sixty-five-year-old ex-madams.

At the same time it is like any other busy lower-class street in Bombay. All day long there are enormous traffic jams, with horns constantly honking, hundreds of taxicabs, and unwieldy two-story buses. Vendors sell brassieres, fountain pens, magazines, and medicines. Water-carriers haul goatskins filled with water into the houses, unloading them from a huge tank truck parked on the street. And always in front of the three movie houses there are long queues of men waiting for the next show to start. (Movies are an important part of Indian life.)

And then there are the customers walking up and down the street, surveying the girls. The customers range in age from thirteen to seventy-five. Some are handsome and some grotesque. They are lower-middle- or lower-class Indians—the area is too poor to attract foreigners, though once in a while some Arabs come by in long white robes. (Arabs are considered very important because they have money and will sometimes even rent a girl for a few days.) The cage girls do everything to attract the men: they beckon and shout and grab at them; sometimes they pull up their skirts and make obscene gestures.”

-Rod Slemmons, Director

This exhibition and related programs are sponsored in part by the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency; Mayer & Morris Kaplan Family Foundation; the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs/Gallery 37; LG electronics, Chicago and American Airlines, the official airlines of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, and our members.

Image Gallery