Reversed Images: Representations of Shanghai and its Contemporary Material Culture

About the Exhibition

Work by:

Olivo Barbieri

Birdhead (Song Tao and Ji Weiyu)

Isidro Blasco

Mathieu Borysevicz

Cao Fei

David Cotterrell

Hu Yang

Jin Shan

Sylvie Levey

Liu Gang

Lu Yuanming

Ma Liang

Shi Guorui

Shu Haolun

Speedism (Julian Friedauer and Pieterjan Ginckels)

Su Chang

Xu Jianrong and Xu Xixian

Xu Zhen

Yang Fudong

Zhou Xiaohu

Zhu Feng

Reversed Images: Representations of Shanghai and Its Contemporary Material Culture examines the city of Shanghai and its development into one of the global economy’s most productive cities in the new millennium. Shanghai is known for its impressive population growth, the increasingly rapid rate of its cultural and environmental transformations, and the tension between Western and traditional Chinese values, lifestyle, and work habits. In addition, the city is caught between a not-so-distant communism and a late-arriving capitalism, between a world founded on its labor force and the world of new technologies. Within this environment, the role of the arts becomes ever-important as artists look to interpret the experience of inhabiting a city and a time that is in the process of defining itself, struggling with the contradictory natures of its past, present, and future. The participating artists in this exhibition take various approaches to capturing a city that seems to continually transform before our eyes.

The role of the arts becomes ever-important as artists look to interpret the experience of inhabiting a city and a time that is in the process of defining itself.

Reversed Images is divided into three thematic areas. The first looks at the romantic notions of Shanghai’s past and how it flourished as a center of commerce for trade between the East and West—represented by the illusion of Shi Guorui’s large-scale camera obscura photograph. It also examines the city’s shift from the past to its development into a hyper-modern city. This theme is represented in the exhibition’s sub-sections: Upside Down/Progressing and Glorifying the City Present/Future. The second theme, titled Artist: Urban Comments, explores how Chinese artists are interpreting their role in Shanghai, living within a contradictory environment that imposes limitations while also producing an extraordinary stage for artistic exploration and visual/conceptual research. The third section, simply called Interiors, describes the secret spaces and unexpected privacy in a city of eighteen million people. The exhibition includes architects, urban planners, and graphic designers, as well as artists using photography.

Romance

Shanghai during the roaring 1920s and ’30s still conjures a city of sin and forbidden pleasures—the mythical Paris of the East. Serving as a prelude and comment for the rest of the exhibition, Shi Guorui’s (China, b. 1964) large-scale panoramic camera obscura image of Shanghai captures both the historic Bund, the old colonial power, on one side of the Huanpujiamg River, and Pudong, the symbol of China’s economic boom, across the river. Created by turning a hotel conference room into a camera, Shi’s photograph is a reversed negative image of a city dealing with its past, present, and future. The image invites the viewer into a game played throughout the exhibition evoking the question: what is real and what is fiction?

Upside down / progressing

The works in this section illustrate Shanghai’s rapid expansion and modernization in the last twenty years and question the perceptions and social implications of a quickly disappearing past and a futuristic present. During the 1970s and ’80s Xu Xixian(China, b. 1942) traveled around Shanghai on the weekends with his young son taking photographs of the landscape. Twenty years later the son, Xu Jianrong (China, b. 1969), began to revisit the now drastically changed locations of his father’s original images, and together they have created a before-and-after portrait of the city. Using an approach more sociological than artistic, their project informs a complex structure of references to the recent past and the already rapidly changing present. Shooting from a helicopter with a tilt-shift lens camera, Olivo Barbieri (Italy, b. 1954) produces selectively focused images that make his urban scenes look like accurate, miniature models. By blurring imperfections and distorting the scale of buildings and people, Barbieri redefines the customary ground-level perspective, creating an urban landscape that to the viewer appears artificial. His work in this exhibition is a surreal vision of Shanghai’s highways at night that juxtaposes the beauty of modernism with contemporary functionalism. Isidro Blasco (Spain, b. 1962) combines architecture, photography, and installation to explore themes of vision and perception in relation to physical experience. Within each sculpture, the viewer is encouraged to become an active participant by interacting within these habitat-like structures that directly mimic similar aesthetics and perspectives found elsewhere in the city. Zhu Feng (China, b. 1974) is fascinated with the makeshift sculptures found randomly on worksites constructed of shipping containers, garbage, removed earth, and detritus. Zhou Xiaohu’s (China, b. 1960) realistic but digitally fabricated photographs describe building sites in the process of being demolished that are surrounded by contemporary architecture. In each image he creates a visual labyrinth of fictional drama. For David Cotterrell’s (United Kingdom, b. 1974)South Facing, a 2005 installation, he has produced an entire city of filler blocks—750 miniature towers—that echo China’s dictate that each new building be at least 15 degrees south-facing, reflecting the emperor’s palaces in which private quarters faced south and the less valued courtiers’ rooms faced east or west. A single spotlight illuminates this overwhelming installation, creating the aura of a silent funerary monument. Su Chang’s (China, b. 1985) mixed-media installation Ruins, 2008, includes a perfect copy of a particular building in Shanghai that was demolished. It represents one of the many buildings that are disappearing from the city’s older neighborhoods, razed to make room for the new city. The proximity of this model to the works by Zhou Xiaohu and David Cotterrell creates a paradox of the real (what does exist) versus the unreal (what has disappeared)—the present versus the past. Jin Shan’s (China, b. 1977) interactive work Build a home for yourself, building for Shanghai, 2005, is a positive representation of the dreams of individuals and refers to the building rush in Shanghai. Within the work the viewer is encouraged to construct his or her ideal home out of wooden building blocks placed on a light table underneath a tent-like structure familiarly used by builders in China. It is a poetic gift for individuals who do not have the actual power to do what the work allows. Birdhead (artist collaborative Song Tao and Ji Weiyu, China, b. 1979 and 1980) offer a direct representation of Shanghai as they nonchalantly capture their neighborhood being demolished to build the 2010 Expo site. Presented in a book, their work is a mixture of carefully composed and casual snapshots taken with a variety of cameras. The thick book, highly inspired by Nobuyoshi Araki’s 2001 book Hardcover, is an extensive accumulative photographic series that delivers a subjective and raw take on urban reality today, a living testament to a generation’s existential bewilderment.

The glorification of the city is everywhere in Shanghai: plastered to construction sites, on radio, television, and Internet sites, and in periodicals.

Glorifying the City (Present/Future)

The glorification of the city is everywhere in Shanghai: plastered to construction sites, on radio, television, and Internet sites, and in periodicals. Liu Gang’s (China, b. 1983) Paper Dream series, 2008 mirrors the real-estate advertisements stretched over scaffolding that typically market a new form of urban living in China. These works bear witness to the rise of a new class of Chinese citizens defined by a rapid social mobility that provokes new anxiety about personal tastes and the need to conform to the trappings of a particular social status. Working in the field of architecture, visual arts, urbanism, and scriptwriting,Speedism (artist collaborative Julian Friedauer and Pieterjan Ginckels, Germany, b. 1980, and Belgium, b. 1982) develop visual universes through the use of 3-D animation rendering different forms of material focused on mythology, urbanism, and geopolitics. By randomly mixing the materials together as if visual DJs, their work becomes collages of information giving rise to diverse points of departure but never with a concrete conclusion. Their work in China reflects the way in which a city’s multilayered realities can clash. As a counter canto, Cao Fei’s (China, b. 1978) RMB City, 2009, is an art community in the 3-D virtual world of Second Life, an online platform where participants create a parallel reality in which to live out their dreams. Within Second Life Cao Fei has constructed a virtual city that will continue to grow and change over its two-year run with the participation and support of leading international art institutions and creative practitioners. The project explores the potential of an online art community, seeking to create the conditions for an expansive discourse about art, urbanism, economy, imagination, and freedom. This particular video presents the making of RMBcity, within a few minutes the viewer witnesses the genesis of the future city that, symbolically, can retrace some of the chaos of Shanghai’s present and future.

Artist: Urban Comments

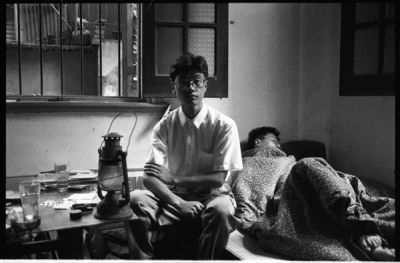

This section focuses on the role of the artist in contemporary Shanghai and includes Yang Fudong’s (China, b. 1971) The First Intellectual, 2000, the first image in his series The Seven Intellectuals adapted from the traditional Chinese stories known asThe Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. This series explores the ambiguous position of intellectuals in contemporary China and their longing for individual freedom in the shifting context of an emerging capitalist economy. As Yang Fudong has stated about the work, “you can see that ‘the first intellectual’ has been wounded. He has blood running down his face and wants to respond, but he doesn’t know at whom he should throw his brick; he doesn’t know if the problem stems from himself or society.” The multimedia piece titled 40+4: Art is not enough! Not Enough! The Making of the Arts in Shanghai 1980s-2008, Artists Interviews attempts to answer Yang’s existential question with a series of interviews with Shanghai-based artists of various generations. This multimedia installation presents a cross section of the Shanghai art scene and probes each artist’s relationship between their work and the evolution of contemporary art in Shanghai.

Interiors

The final section of the exhibition is the private, intimate, and secret representation of the city of Shanghai that brings together Confucian society and modernity, making apparent the complexity of both individualism and social structures. With their elaborate sets and costumes, Ma Liang’s (China, b. 1972) photographs become playful, audacious fables that often focus on the florid and open personality of the young Chinese urban generation. With these aesthetics Ma also retraces historical or renowned Chinese legends that refers to the decadence of modern Shanghai, creating unexpected associations. His work comments on Chinese culture’s misinterpretation of the prevailing consumer culture but also plays with extreme aesthetics to make humanity look as if an artifact or locus of beauty. Photographer Lu Yuanming (China, b. 1950) records Shanghai urbanites assaulted by profound economic change who nevertheless follow their usual habits. Unconcerned with changes in their external world and living on the eve of radical upheavals in Chinese society, Lu Yuanming’s subjects almost appear willing to lose themselves in times that have passed. The pictures by Lu are taken in the early ’90s and can be seen as a prelude to Hu Yang’s (China b. 1959) photographic series Shanghai Living, 2005. Hu documented the living spaces of 500 families, ranging from migrant workers to foreign diplomats living in Shanghai in 2005. The photographs have an anthropological and sociological approach that attempts to convey the dramatic changes of domestic living that occurred following the processes of modernization. In a second work included in the exhibition by Yang Fudong, Honey, 2003, portrays a generation of individuals in their late 20s and 30s who are part of the emerging middle class in China and who hover between the past and present. Taking place in a high-rise apartment building (the quasi-capitalistic environment of the new middle class) Yang’s work epitomizes how the recent and rapid modernization of China has overthrown traditional values and culture. Responding to Yang’s work, the photographs from Xu Zhen’s (China, b. 1977) series Super Absorbent, 2003, document the underworld of Shanghai’s nightlife with blurred, almost faded images of Karaoke bars and nightlife in general. Each of the pictures is constructed of texts from virtual conversations taken from the Internet, and they are sometimes incredibly explicit in their erotic or pornographic

content. Zhang Qing’s (China b. 1977) works are always irreverent and dissociated from linear thinking. In the work presented here the artist plays with the unbearably small size of Shanghainese apartments and turns them into soccer playgrounds where youngsters have fun. The video and stills are gracefully composed and create a lyric request for air and freedom.

Epilogue

The epilogue of this exhibition comprises one short film and two documentaries that comment on Shanghai: Shu Haolun’s(China, b. 1974) Nostalgia, 2006 (70 minutes) is an ode to the rapidly disappearing Longtang and Shikumen structures of Shanghai’s past being demolished and replaced with modern high-rises. Shikumen houses are two- or three-story townhouses, with the front yard protected by a high brick wall whereas the Longtangs are villagelike communities made up of lanes in the middle of a sprawling metropolis. Complementing Shu’s piece, filmmaker Sylvie Levey (France) spent five years documenting the Wang family, three generations of Chinese living under one roof in the old city of Shanghai who are suddenly confronted by the imminent demolition of their home. The film Shanghai Waiting for Paradise, 2007 (26 minutes) tracks their hopes, struggles, and frustrations with China and the rest of the world, as well as the tremendous stresses on Chinese families when globalization arrives abruptly, even violently. Mathieu Borysevicz’s (United States, b. 1971) Taian lu, 2008 (12 minutes), is a lyrical account of a pregnant woman’s journey through the city of Shanghai. The father-to-be (the artist) wanders through the city looking for his lost pregnant wife and creates a surreal portrayal of the

contradictions of daily life in Shanghai.

All cities find themselves between a celebrated past and a dynamic present that demands rejuvenation.

All cities find themselves between a celebrated past and a dynamic present that demands rejuvenation. If they stop too long to preserve what is unique and beautiful the world passes them by. If they destroy themselves too rapidly, they run the risk of losing their hard-earned, long-term identity. The artists in this exhibition explore the metaphoric possibilities of this dilemma within Shanghai—and themselves.

-Davide Quadrio, Director Arthub, Shanghai/Hong Kong/Bangkok and Natasha Egan, Associate Director and Curator, Museum of Contemporary Photography

Image Gallery