Taryn Simon: The Innocents

About the Exhibition

“I was asked to come down and look at the photo array of different men. I picked Ron’s photo because in my mind it most closely resembled the man who attacked me. But really what happened was that, because I had made a composite sketch, he actually most closely resembled my sketch as opposed to the actual attacker. By the time we went to do a physical lineup, they asked if I could physically identify the person. I picked out Ronald because, subconsciously, in my mind, he resembled the photo, which resembled the composite, which resembled the attacker. All the images became enmeshed to one image that became Ron, and Ron became my attacker.”

—-Jennifer Thompson, on the process to identify the man who raped her.

During the summer of 2000, I worked for the New York Times Magazine photographing men and women who were wrongfully convicted, imprisoned, and subsequently freed from death row. After this assignment, I began to investigate photography’s role in the criminal justice system.

The criminal justice system had failed to recognize the limitations of relying on photographic images.

I traveled across the United States photographing and interviewing men and women convicted of crimes they did not commit. In these cases, photography offered the criminal justice system a tool that transformed innocent citizens into criminals, assisted officers in obtaining erroneous eyewitness identifications, and aided prosecutors in securing convictions. The criminal justice system had failed to recognize the limitations of relying on photographic images.

For the men and women in these photographs, the primary cause of wrongful conviction was mistaken identification. A victim or eyewitness identifies a suspected perpetrator through law enforcement’s use of photographs and lineups. These identifications rely on the assumption of precise visual memory. But through exposure to composite sketches, mugshots, Polaroids, and lineups, eyewitness memory can change. Police officers and prosecutors influence memory, both unintentionally and intentionally, through the ways in which they conduct the identification process. They can shape, and even generate, what comes to be known as eyewitness testimony.

The high stakes of the criminal justice system underscore the importance of a photographic image’s history and context.

The high stakes of the criminal justice system underscore the importance of a photographic image’s history and context. The photographs rely upon supporting materials, captions, case profiles and interviews, in an effort to construct a more adequate account of these cases. This project stresses the cost of ignoring the limitations of photography and minimizing the context in which photographic images are presented. Nowhere are the material effects of ignoring a photograph’s context as profound as in the misidentification that leads to the imprisonment or execution of an innocent person.

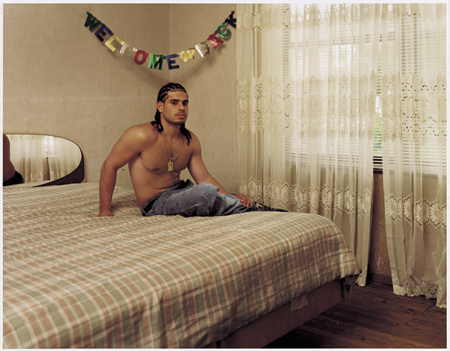

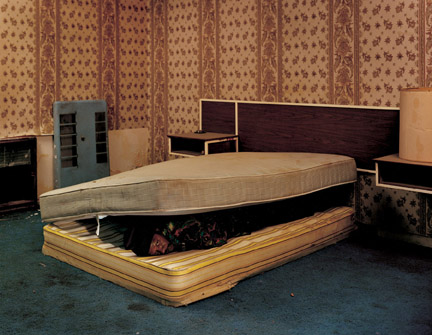

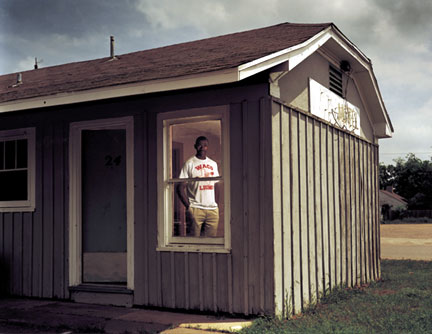

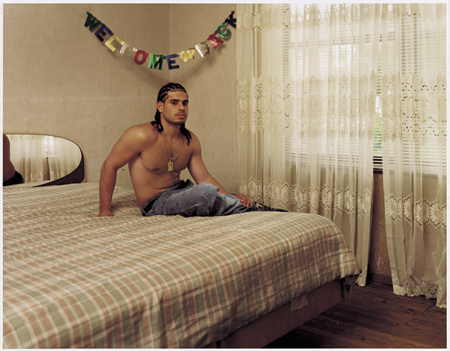

I photographed each innocent person at a site that came to assume particular significance following his wrongful conviction: the scene of misidentification, the scene of arrest, the alibi location, or the scene of the crime. In the history of these legal cases, these locations have been assigned contradictory meanings. The scene of arrest marks the starting point of a reality that is based in fiction. The scene of the crime, for the wrongfully convicted, is at once arbitrary and crucial; a place that changed their lives forever, but to which they had never been. Photographing the wrongfully convicted in these environments brings to the surface the attenuated relationship between truth and fiction, and efficiency and injustice.

Evidence does not exist in a closed system. Like photography, it cannot exist apart from its context, or outside of the modes by which it circulates.

The wrongfully convicted in these photographs were exonerated through the use ofDNA evidence. Only in recent years have eyewitness identification and testimony been forced to meet the test of DNA corroboration. Because of its accuracy, DNAallows a level of comfort that other forms of evidence do not offer. In the exoneration process, DNA evidence pressures the justice system and the public to concede that a convicted person is indeed innocent. In our reliance upon these new technologies, we marginalize the majority of the wrongfully convicted, for whom there is no DNAevidence, or those for whom the cost of DNA testing is prohibitive. Even in cases in which it was collected, DNA evidence must be handled and stored and is therefore prey to human error and corruption. Evidence does not exist in a closed system. Like photography, it cannot exist apart from its context, or outside of the modes by which it circulates.

Photography’s ability to blur truth and fiction is one of its most compelling qualities. But when misused as part of a prosecutor’s arsenal, this ambiguity can have severe, even lethal consequences. Photographs in the criminal justice system, and elsewhere, can turn fiction into fact. As I got to know the men and women that I photographed, I saw that photography’s ambiguity, beautiful in one context, can be devastating in another.

-Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon: The Innocents was organized by P.S.1 Chief Curator Klaus Biesenbach and P.S.1 Curator Amy Smith-Stewart. This work was generously supported by the Innocence Project and a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in Photography. This exhibition is made possible by the James Family Foundation and the American Center Foundation and the Ava Olivia Knoll Fund. Special thanks to Althea Wasow, Sarah Baden, Louis Gabriel, Kevin Hooyman, Joseph Logan, Baron & Baron, Umbrage Editions, Adorama, Color Edge, and Gagosian Gallery.

The exhibitions, presentations, and related programs of the Museum of Contemporary Photography are sponsored in part by the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency; City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs/After School Matters; American Airlines, the official airlines of the Museum of Contemporary Photography and our members. The Innocents exhibition at the MoCP was generously supported by the Hugh M. Hefner Foundation.

Image Gallery