Work By:

Merry Alpern

Sophie Calle

Walker Evans

Chris Verene

Shizuka Yokomizo

The Furtive Gaze

Photography, with its special capacity for identification, observation, and implication, rewards both artist and sleuth. Allowing unprecedented access to and evidence of otherwise private and restricted moments, the camera has proven itself the perfect tool for the delicious pleasure of witnessing someone caught off guard.

As the early technology of photography developed, so did its capacity to furtively invade our lives without our knowledge or consent. In the late 1880s advances in the production of gelatin-coated dry plates and roll films, and the subsequent standardization of film size, film processing, and shutter speeds, resulted in a medium that was affordable and widely accessible to the public. By the 1890s hand-held cameras were mass produced and light weight, and the introduction of specialty “detective” cameras made the surreptitious portrait fashionable. Cameras were built into purses, walking sticks, pocket watches, men’s ties, and, in one notably twisted case, molded into the shape of a revolver.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the arrival and proliferation of the 35mm camera paralleled the beginnings of the great age of the picture press. Films became faster, flashbulbs cheap and convenient, and tripods were no longer necessary in low light. The quickly made image, either from a concealed position or in the heat of the action, developed a hunger for thrilling photojournalism. Notoriously, in 1928 a photographer, using a camera hidden in his pant leg, illicitly photographed the execution by electrocution of Ruth Snyder, and the photograph was printed on the front page of the New York Daily News. As privacy was increasingly invaded, even death could not escape the camera’s eye.

Meanwhile, many artists began using stealth along with the improved technology of photography to capture compellingly spontaneous portraits. Early twentieth-century photographers such as Paul Strand and Ben Shahn modified their cameras with decoy lenses and right angle viewfinders in order to photograph people clandestinely on the streets of New York. In the late 1930s Walker Evans took his 35mm Contax into New York’s subways and covertly photographed his fellow passengers, creating Many Are Called, a remarkable body of work that resonates through the unguarded expressions of his subjects. Similarly, in the 1950s and 1960s, photographers such as Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank, and William Klein immersed themselves in the bustle of the city and captured poignantly candid moments in the lives of many unsuspecting strangers.

For the philosopher Roland Barthes, the power of furtive photography stems from its ability to disclose part of its subject’s subconscious:

I imagine (this is all I can do, since I am not a photographer) that the essential gesture of the Operator is to surprise something or someone (through the little hole of the camera), and that this gesture is therefore perfect when performed unbeknownst to the subject being photographed. From this gesture derive all photographs whose principle (or better, whose alibi) is “shock”; for the photographic “shock” … consists less in traumatizing than in revealing what was so well hidden that the actor himself was unaware or unconscious of it.

Undoubtedly the subject’s lack of awareness and consequent loss of control allows a trolling artist the opportunity to make an extremely potent photograph. But what is at the root of the delectability of this “perfect” gesture described by Barthes? Perhaps surreptitious photographs also reveal something about our own subconscious by tapping into a universal fear of being caught unaware or by exaggerating the disconcerting feeling of being watched.

Through both media and art, photography and video recording have certainly made our lives more public; privacy today is an increasingly precious commodity. Decades after Alan Funt captured amusing human behavior on Candid Camera and PBSmonitored the lives of the Louds in their series An American Family, reality television, news exposés, and web-cams have proven that mediated voyeurism for the purposes of entertainment has great appeal to the popular imagination. We reluctantly accommodate ourselves to being watched at the ATM, the airport, in stores, and on the street. But ironically our appetite for violating the privacy of others and observing them in unexpected and extremely personal circumstances does not seem to wane.

“The Furtive Gaze” presents the work of five contemporary artists who use strategies of cajolery, collaboration, and deceit to explore the boundaries of privacy. All five artists hide their photographic actions to a certain degree-concealing their camera, or disguising themselves or their motivation. Blurry, grainy, or “blocked” by foreground objects, their works clearly signal that we are looking at a document created on the sly with a camera used primarily as a surveillance tool.

In her Shopping series (1997 – 99), Merry Alpern (United States, born 1955) employs fuzzy video stills to explore themes of surveillance and self-scrutiny. Concealing a video camera in her purse, Alpern visits department stores where she captures women enthralled in a mesh of consumerism and vanity. Printed as video stills, the grainy images titillate with messages of the taboo and confidential. The women try on clothes, inspect their bodies, squeeze into stockings and skirts, and gently fondle luxury products—lost in a host of private emotions and desires while existing in a very public space.

Although we know it is there, security surveillance is often imagined as dispersed and remote. Michel Foucault describes how in an a society marked by surveillance, power relies upon the anonymous, inspecting gaze, “a gaze which each individual under its weight will end by interiorising to the point that he is his own overseer, each individual thus exercising this surveillance over, and against, himself.” Recorded completely without her subjects’ knowledge, Alpern’s unseen camera parallels the examining gaze described by Foucault. Meanwhile, the women’s behaviors reveal that being observed by others, both known and unknown, influences the choices we make about how we look, act, and consume.

Like Alpern, Chris Verene (United States, born 1969) employs his camera furtively, but without entirely concealing it from view. For his series Camera Club (1995 – 1997), Verene infiltrated the world of “camera clubs,” groups of men who lure young women into modeling nude or seminude by placing classified ads in newspapers and pretending to be professional fashion photographers. Verene posed as a camera club photographer, joined the group and played the part, but then turned his camera on the photographers themselves. By positioning himself behind the men and pretending to be tinkering with his camera – loading his film, testing his flash — Verene could easily release his shutter without arousing the suspicion of his already distracted colleagues.

The resulting pictures telescope the usual photographer’s gaze and emphasize the predatory nature of photography. Verene’s compositions mirror the power dynamics of the situation: the men’s backs, hairy legs, and balding heads dominate the picture plane and their lurching posture reveals their avidity. In contrast, the women in the background are small in scale; Verene protects their identities by keeping them generally out of focus.

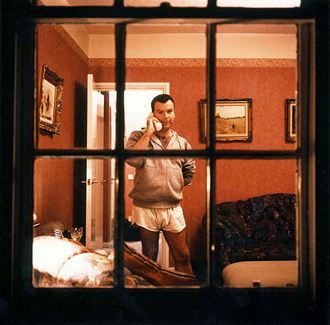

The power imbalance of photography, so craftily articulated by Verene, is leveled somewhat in the photographs of Shizuka Yokomizo (Japan, born 1966, United Kingdom resident). Her series Stranger (1998 – 2000) has at its core collaboration. Yokomizo sends her subjects an anonymous letter proposing they stand in their front window at a specified date and time, at which point the artist arrives outside, photographs for a few minutes, and then leaves. The subjects are instructed to wear their usual clothing, remain calm, and turn on all their lights. Because the hour selected is during the night, Yokomizo’s subjects can discern the photographer only as a dark silhouette setting up her tripod and camera, exposing her film, and leaving. The barriers Yokomizo includes in the foreground of her pictures—window moldings, curtains, and security gates-as in Verene’s Camera Club pictures, clearly articulate layers of distance and enhance the feeling of voyeurism.

The success of Yokomizo’s Stranger series depends on the willingness of her subjects to place extraordinary trust in a stranger. Their body language ranges from suspicion to hostility to amusement to nervousness. Asked to perform, they acquiesce, and in return the photographer performs for them. The photographs are intimate in their complicity.

This excitement of briefly and intimately interacting with a stranger is explored in the video For a Moment Between Strangers (2001) by Melanie Manchot (Germany, born 1966, United Kingdom resident). Manchot walked through the streets of cities throughout the world asking random people to give her a kiss, all the while taping them with a lens hidden in the shoulder strap of a bag. Perhaps predictably, yet engagingly, their responses range from disgust to dismissal to playful consent.

In Manchot’s installation, the entire sequence of each encounter is seen, with sound, on a monitor. Behind the monitor, a close-up of the people leaning in to give her a kiss or turning their heads away is projected silently. At the last moment, her hidden lens can capture only the chin and neck of her subjects, frustrating our desire to witness the kiss. Edited into a mesmerizing rhythm of approach and retreat, the sequence is charged by the fact that the neck, an extremely vulnerable and sensual part of the body, is exposed, infusing the encounter with an invasive intimacy in contrast to the seeming lightness of the situation.

In Suite Vénitienne (1980) by Sophie Calle (France, born 1953), it is the unsuspecting stranger who collapses the distance between himself and the photographer. The piece chronicles Calle’s shadowing of a man she met randomly one evening in Paris. He tells her he is leaving for Venice the next morning, and she spontaneously decides to follow him there. Disguised in a wig and overcoat, Calle searches for him in scores of hotels until she finally spots him. She follows the man and his companion around the city for days, talking photographs all the while, sometimes of the couple and sometimes of the things they photograph. She charts on a map the routes they take and jots down notes about their behavior. Finally, one day the man senses that he is being followed and confronts her. He photographs her and tells her that he recognized her by the one thing she hadn’t disguised — her eyes.

As a compelling counterpoint to Suite Vénitienne, Calle’s The Shadow (La Filature) (1981) turns the tables on the concept of photographer as voyeur: here the artist assumes the role of the observed person. In this piece Calle had her mother hire a private detective to follow Calle and report on her daily activities. As she wandered through the streets of Paris, Calle led the detective on a trail of places of personal significance to her, such as the garden where she had her first kiss and to her studio. In the end, Calle’s colorful description of the day is contrasted with the detective’s clinical, factual notes, revealing the difficulty of compiling a portrait of someone through the distance of unilateral observation and the telephoto lens. Slyly Calle obliterates the intended documentary nature of the detective’s report, and tests both the truthfulness of photography itself, and the honesty of our public selves.

Although the pictures made by these artists are achieved furtively, the behaviors of their subjects are only semiprivate, as all of their actions take place in locations in which they know they are being watched. The artists in this exhibition emphasize the clandestine nature of their intention by creating pictures that are often fuzzy, obscure, or mysterious.

Instead of simply pointing a camera through a window or from a concealed location, these artists in this exhibition enter the realm of their subjects and are active participants in the scenes they record. They boldly insert their presence, taking up a position wedged between the viewer and their subjects, thereby making their photographs less transparent and us more aware that we are observing the observer. The formal devices of graininess, blurriness, and partial obscurity prevent us from being lost in the picture, and catapult us back out of the frame and self-consciously into the circumstances of its production. Unlike performance art of the 1970s, however, these photographs are not simply documentation of an action, they are the genesis of the project and the end artistic product. They extend exploration of previous notions of the “male gaze” and traditional gender roles, and open up alternative viewing positions. The voyeur in these works is the protagonist, yet the voyeur’s position is also our own, implicating our illicit interest in the scene.

-Karen Irvine, Associate Curator