Witness: Contemporary Mexican Photojournalism

About the Exhibition

Work by:

Eniac Martinez

Yolanda Andrade

Marcela Taboada

Albert Ibanez

Francisco Mata Rosas

Jorge Lepez Vela

Maya Goded

Jaime Vayarez

Antonio Turoc

The evidence of photographs can both enhance and confuse the way we look at the lives of others. Since the early 20th century, a robust and highly independent tradition of photojournalists and documentarians has developed in Mexico, dedicated to reporting the truth of their rich and complex culture. Witness: Contemporary Mexican Photojournalism explores the development and contemporary forms of this practice.

This tradition begins with Agustin Victor Casasola, whose career in Mexico, 1900-1936, produced a thorough record of the causes, the fighting, and the results of the Revolution of 1910. His and his employees’ images were published widely in the international news media, drawing great attention to Mexico. The tradition continued through the reportage and documentary work of Manual Alvarez Bravo, Nacho Lopez, Hector Garcia and Graciela Iturbide, all of whom produced expressive, art photography as well. The central focus of this exhibit will be the latest generation: Antonio Turok, Maya Goded, Jorge Lépez Vela, Marcela Tabaoda, Alberto Ibañez, Jaime Vayarez, Francisco Mata, Yolanda Andrade, and Eniac Martinez.

Witness is a significant exhibition for the North American photography community in that it demonstrates the vitality of this genre in Mexico today, something that has not been done specifically in the few exhibits to come out of Mexico in the past two decades.

Witness is a significant exhibition for the North American photography community in that it demonstrates the vitality of this genre in Mexico today, something that has not been done specifically in the few exhibits to come out of Mexico in the past two decades. Most of these were concerned with contemporary art photography, manipulated work, historic photography, or gender specific work. In addition, even though some of the artists in this exhibit have been published individually in Mexico, there has not been an opportunity to see them together as a group, which reveals a very strong common voice and similarities of vision. The show also gives the growing community of Mexican and Mexican-American photographers in Chicago an opportunity to see new work from Mexico.

Due primarily to the popularity of the two recent movies, Amor Perro and Y Tu Mama Tambien, galleries and in the United States and Europe have suddenly taken a greater interest in Mexican art, including contemporary Mexican photography. It is interesting that most of the photographers who have broken out of both Mexico and foreigner’s idea of Mexico, as diverse as they may be, fall squarely within the oldest and strongest tradition of photography in that country: social documentary. Even Daniela Rossell’s portraits of her wealthy friends—a nice amalgam of Diane Arbus and Tina Barney, are clearly a social record and critique. Others closer to the canon are Enrique Metinides with his shocking crime scenes and Melanie Smith’s aerial views of the vast poor neighborhoods surrounding the capital.

It is interesting that most of the photographers who have broken out of both Mexico and foreigner’s idea of Mexico, as diverse as they may be, fall squarely within the oldest and strongest tradition of photography in that country: social documentary.

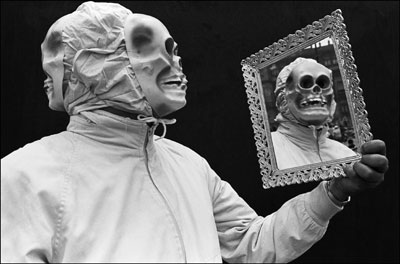

Outsiders are generally unaware of the sheer volume of this kind of work that has been going on since the Casasola Brothers documented the Revolution (really Civil War of Reform) of 1910, and before in the satirical social commentary of the relief prints of Jose Guadalupe Posada. The tradition encompasses both documentary projects that result in publications and exhibitions and photojournalism—in fact the line between these two is often hard to find. Americans aware of photography in general will have heard only of Manuel Alvarez Bravo who worked a little to the side of this tradition while tapping into its formal strategies and subject matter. But the list is long, including Natcho Lopez, Losa Alvarez Bravo, Hector Garcia, Mariana Yampolsky, Graciela Iturbide, and many others.

While there is a similar tradition in the United States, beginning with Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, and progressing through the Farm Security Administration, to Eugene Smith, Danny Lyon, Bruce Davidson, Mary Ellen Mark, and Susan Meisalas, there are some serious differences. First of all, Mexican photography, except for a brief brush with Edward Weston, managed to escape Pictorialism. The formal design and symbolic strategies brought to bear on documentary by former Pictorialists Paul Strand and Dorothea Lange are clearly seen in later work by Danny Lyon, for example. Also, the shift from concerned documentary—pictures intended to decry conditions and invoke change—to art that happened in the career of Robert Frank (as pointed out by Martha Rosler and others) never really happened in Mexico. As a consequence of both of these, Mexican documentary is still interested in what is in front of the lens, and picture design tends to augment knowledge of a given subject rather than transpose it to moral decoration and formal experimentation.

Mexican documentary is still interested in what is in front of the lens, and picture design tends to augment knowledge of a given subject rather than transpose it to moral decoration and formal experimentation.

Artists may use documentary strategies and documentarians may use poetic strategies, but they have no real need to be each other.

It is important to note that photography enlisted to make work intended primarily as art is a shorter but no less strong tradition in Mexico. Of the nearly five hundred exhibitions nation-wide in the 2003 FotoSeptiembre photography festival, nearly half were in this tradition. Perhaps because of a lack of a commercial gallery system of the magnitude found in the United States, the line between these two traditions is not clearly drawn. Artists may use documentary strategies and documentarians may use poetic strategies, but they have no real need to be each other. Also, some Mexican artists have worked on both sides of this line—Pablo Ortiz Monastario is a prime example. While social documentary projects such as those of Graciela Iturbide and Eniac Martinez, and others, have been shown in art museums in Mexico, they have always been shown in the context of their social concerns for their subject. This is not always true when they are shown in art museums outside of Mexico.

Witness offers a look at the latest generation of the large and diverse family of Mexican social documentary.

—Rod Slemmons, MoCP Director