Art, Activism, Policy, Power Educator Resource: Documenting Migration Stories in Portraits and Interviews

About the Artists

Regina Agu was born in Houston, Texas and raised between the United States, Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, South Africa, and Switzerland. She relocated to Chicago in 2020, where she now lives and works.

Her work spans exhibitions, publications, performances, and public readings, presented internationally at venues such as the New Museum, The Drawing Center, the High Line, Project Row Houses, FotoFest, and the American University Museum. Recent exhibitions include the 2021 Atlanta Biennial: Of Care and Destruction and the 2021 Texas Biennial: A New Landscape, A Possible Horizon. Her first solo museum exhibition, Passage, was presented at the New Orleans Museum of Art (2019–2020).

Agu is the 2023 Joyce Award recipient with the Museum of Contemporary Photography. Her projects have been supported by Artadia, Houston Arts Alliance, The Idea Fund, and the University of Houston’s Kathrine G. McGovern College of the Arts + Project Row Houses Fellowship. She has held residencies at Hyde Park Art Center, Joan Mitchell Center, A Studio in the Woods, The Drawing Center, and Atlantic Center for the Arts, among others.

She holds a BS from Cornell University and an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

In 2025, Agu’s launched Regina Agu: Shore | Lines at MoCP as her first Midwest solo exhibition and its companion publication Regina Agu: Field Notes for Shore Lines published by Kris Graves Projects.

Jonathan Michael Castillo is a visual artist, photographer and educator based in Chicago. He was the 2019-2021 recipient of the Diane Dammeyer Fellowship in Photographic Arts and Social Issues. Jonathan was included in the 2021 Hyde Park Art Center’s Ground Floor Biennial in Chicago and was a finalist for the WMA Commission in Hong Kong. His work has been featured with The New Yorker, Wired, The Chicago Tribune, CBS: Los Angeles, and Brazil’s G1 Globo. He has been interviewed on the BBC’s “World Update” and Los Angeles public radio stations KPCC and KCRW. Jonathan was recently commissioned to create a large-scale permanent installation of his work at O’Hare International Airport as part of the Terminal 5 expansion project. In 2023 he was commissioned to make work for the city of Chicago’s Citywide Plan in partnership with the Department of Cultural Affairs and the Department of Planning and Development. Exhibitions include those at the Art Institute Chicago, Photo LA 2020, the Center for Creative Photography, Aperture Gallery, House of Lucie, Filter Photo Gallery, Ralph Arnold Gallery and the California Museum of Art Thousand Oaks. Jonathan is represented by Samuel Maenhoudt Gallery in Belgium. His education includes a BFA from California State University Long Beach and MFA from Columbia College Chicago.

Dawit L. Petros is a visual artist, researcher, and educator whose practice is informed by studies of global modernisms, diaspora, and postcolonial theory. An Eritrean emigrant who spent formative years in Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Kenya before settling in Canada, Petros draws on lived experiences of migration to critically examine the entanglements between colonialism and modernity. His installations combine photography, moving image, sculpture, and sound, employing painterly, performative, and site-responsive strategies that echo the extensive travels integral to his work.

He holds an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Tufts University, a BFA from Concordia University, a BA in History from the University of Saskatchewan, and completed the Whitney Independent Study Program. Petros’s work has been shown internationally at venues including the Studio Museum in Harlem, Huis Marseille Museum of Photography (Amsterdam), the 13th Biennial of Havana, the National Museum of African Art (Washington, DC), the Durban Art Gallery, and the Lianzhou International Photo Festival.

His awards include the Terra Foundation Research Fellowship, the Paul De Hueck and Norman Walford Career Achievement Award in Art Photography, and the Duke and Duchess of York Prize in Photography. Petros is represented by Tiwani Contemporary (London) and Bradley Ertaskiran (Montreal).

In 2024, Petros premiered his solo exhibition at MoCP and publication by Mousse Publishing, Dawit L. Petros: Prospetto a Mare curated by MoCP Chief Curator and Deputy Director Karen Irvine.

Image Gallery

About the Program

MoCP’s Art, Activism, Policy, Power 2024 program welcomed artists Regina Agu, Jonathan Michael Castillo, and Dawit L. Petros to work with students from South Shore College Prep, Prosser Career Academy, and Lincoln Park High School to create photographic portraits and interviews of people in their families, neighborhoods, or social circles, to capture stories about how they arrived to Chicago.

This resource can be adapted to be used by educators in any classroom.

Introductory Questions

Both Agu and Petros represent stories of migration in their artwork.

Art there people in your life that have moved to Chicago from a place that is very different from this city?

How might an artist express stories differently from the people who have lived experiences?

Why do you think Chicago is a beacon for migrating or displaced communities?

Learn

Art

What does it mean to be an artist activist?

Artists have the potential to creatively collect and weave together community memory. When engaging with other people’s stories, it is important to slow down and be present and intentional with your interactions. You are giving people a platform to share stories that may have otherwise gone unheard, and with that comes responsibility.

There are many forms of activism that range from active demonstrations, organizing boycotts, divestment demands, and protests to self-education and promoting awareness of paradigms and systems of oppression in place throughout history and today.

It perhaps is not as common to think of compassionate listening as a form of activism. In this approach, taking time to ask questions and learn from people in our communities about what is important to them, where they came from, and what challenges they face can be a deeply effective way to extend love and care to your surroundings and de-center a culture of separateness.

Artists have the potential to creatively collect and weave together community memory. When engaging with other people’s stories, it is important to slow down and be present and intentional with your interactions. You are giving people a platform to share stories that may have otherwise gone unheard, and with that comes responsibility.

Activism

What forms of activism have you seen, taken part of, or felt drawn to?

There are many forms of activism that range from active demonstrations, organizing boycotts, divestment demands, and protests to self-education and promoting awareness of paradigms and systems of oppression in place throughout history and today.

It perhaps is not as common to think of compassionate listening as a form of activism. In this approach, taking time to ask questions and learn from people in our communities about what is important to them, where they came from, and what challenges they face can be a deeply effective way to extend love and care to your surroundings and de-center a culture of separateness.

Artists have the potential to creatively collect and weave together community memory. When engaging with other people’s stories, it is important to slow down and be present and intentional with your interactions. You are giving people a platform to share stories that may have otherwise gone unheard, and with that comes responsibility.

Besides compassionate listening, what are some other forms of sustainable activism?

Policy

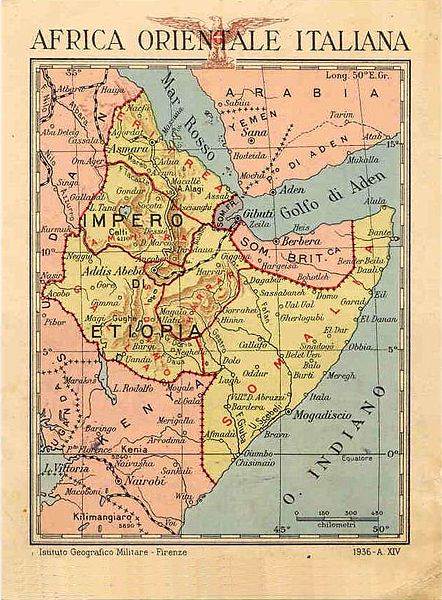

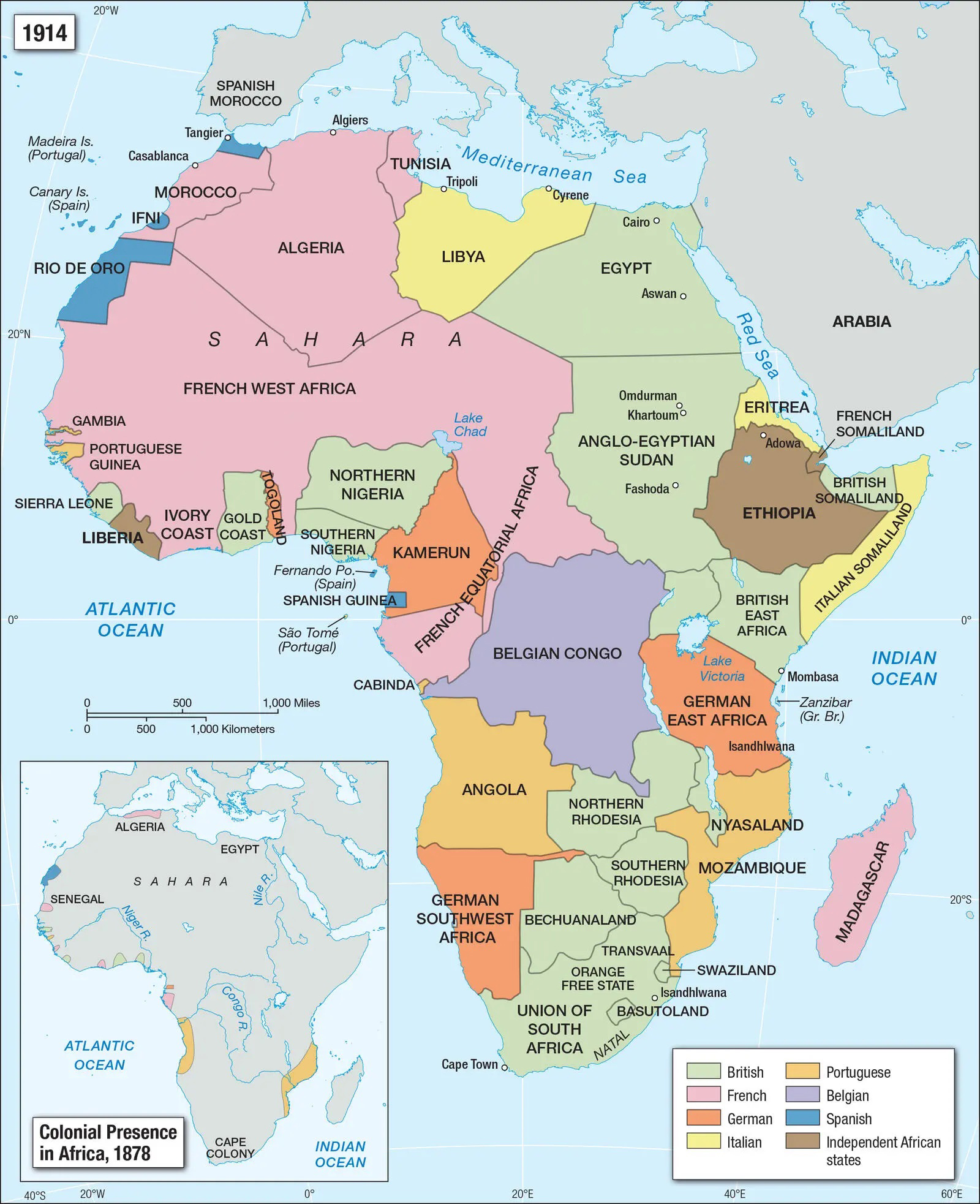

Dawit L. Petros’s work is informed by the history of European colonization in Africa and how it shaped global migration. From 1833 until 1914, 90 percent of the African continent was under European rule, as countries raced to pillage resources like gold, silver, rubber, palm oil, and later, cotton at the expense of the livelihood of local communities.

In around 1885, Italy began colonizing parts of East Africa, first in present-day Eritrea and parts of Somalia with intent to expand into what was then the Ethiopian Empire. Ethiopia defeated Italy in the First Italo-Ethiopian War from 1895-1896, and the countries again were at war from 1935-1936, when Italy consolidated Ethiopia with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland into the province of Italian East Africa.

During World War II, Italy lost control of its colonies in Africa. In 1952, the United Nations placed Eritrea under control of Ethiopian Empire, which has since been the root of many conflicts. As a result, between 1965 and 1991, roughly one-quarter of Eritreans fled the Horn of Africa due to war, famine, political unrest, and persecution. By the year 2000, 30,000 Eritreans lived in the United States—many of them in Chicago.

Discussion questions:

According to the Vera Institute, in 2023: “1.7 million immigrants reside in Chicago, or 18 percent of the total population. One in three children in Chicago has at least one immigrant parent.”

The history of war and colonialism outlined above is just one example of how political forces in one locations can shape the demographic makeup of neighborhoods and communities across the world.

What other global histories might shape the way you live in and experience Chicago?

Image Gallery

Power

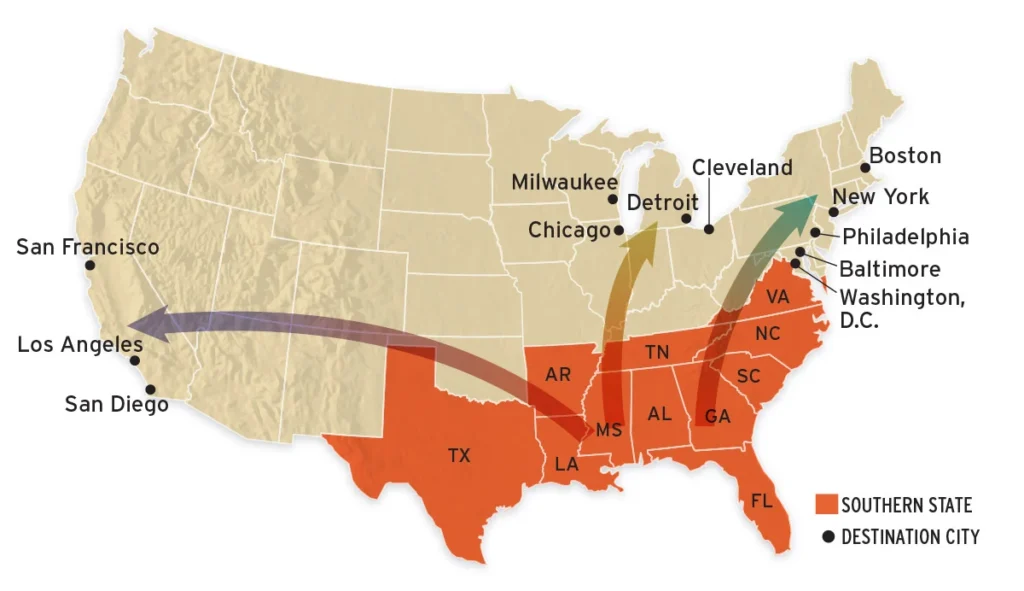

Regina Agu’s work is informed by the history of the Great Migration, which occurred in the United States from 1915 until 1970. During this time, an estimated six million Black Americans left the segregated Jim Crow South for more opportunities and more freedom. During the first wave of the migration, people traveled by railway, with Chicago as one of its primary routes. Later, after the addition of the interstate highway system, people were able to more easily travel across the country by bus. Chicago was a destination throughout, and the city was permanently transformed, with its population of Black residents growing from just two percent of the overall population in 1910 to 33 percent by 1970.

Discussion questions:

Are there any ways you see the American South represented in Chicago today, such as in food, architecture, or cultural traditions?

Accents, sayings, and slang vary across the United States. For example, the way people speak in Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles can differ widely from southern cities like New Orleans or even East African communities. How might the Great Migration or Immigration have had an affect on regional African American Vernacular English (AAVE)?

Where are people in your neighborhood from? For how many generations have they lived there?

Engage

Capturing your own portraits

Now that you know a little more about the artists you will be working with, it’s time to think about how you can add your voice. The prompts below will help guide you in creating photographic portraits and oral history interviews that capture migration stories in your community.

Please also contribute your personal history to our collective migration map here.

Identify who to interview

Working in groups, have students discuss who they know in their families, neighborhoods, or social circles who have moved to Chicago from another city, state, or country. Ask them to write down as many names as they can identify, pushing them to think about whose stories they believe most strongly should be seen and heard.

What do they already know about the person?

How comfortable will they be inviting them to participate in this project?

How accessible is the person they want to photograph and interview?

Are there any privacy concerns?

For example, will the person be open to having their story shared in a gallery and online?

Was the person a part of any significant history that you want to highlight?

What research can you do on that history so you can ask questions that draw out these lived experiences?

Set up a location to photograph

Before inviting a person to be photographed, take some time to consider where the photograph should take place. What is seen in the background of the image can potentially give a lot of information and say a lot about the person in the photograph. Will you photograph them in their home? Please of work? Outdoors in a location that is significant to them?

Also make a plan for what time of day you would like to photograph. If photographing outside in the early morning or early evening, your lighting will appear more golden and romantic than if you photograph in mid-day when the sun is bright (and the person may be squinting). If you are photographing indoors, are there ways to adjust the lighting so that the camera can more accurately capture details in the setting?

And finally, once your person has arrived and you are about to photograph, consider how they should sit or stand. What do you want their body language to communicate? Will you show their whole body or just their head and torso? If there are privacy concerns, can you make a portrait of someone by photographing an object they own, or obscuring their face from view?

Create an oral history recording of their migration story

Either before, during, or after making the photographic portrait, ask your participant questions about their story that you can share as a component of the final artwork presentation. Excerpts from the interview can either be presented as text panels that accompany the portrait (such as in Jess T. Dugan’s To Survive on the Shore series) or as a QR code that someone could scan with their phone to play and listen to while they look at your portrait.

Before recording, write out a list of questions you plan on asking. Try to avoid “yes and no” questions and instead ask open-ended questions that will get the person sharing more details about their life. For example, instead of saying: “Did you like Chicago when you first moved here?” You could say: “Tell me how you felt when you first arrived to Chicago.”