Photographers of the New Bauhaus

This resource integrates the study of photographs from the collection of the MoCP into secondary and post-secondary fine arts, language arts, and social science curriculum. This guide contains questions for looking and discussion, historical information, and classroom activities and is aligned with Illinois Learning Standards. A downloadable PDF version can be found here.

The museum is generously supported by Columbia College Chicago, the MoCP Advisory Committee, individuals, private and corporate foundations, and government agencies. Special funding for this guide was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

The New Bauhaus, later called the Institute of Design (ID) was one of the most important schools of design and photography in the United States during the twentieth century.

Founded in Chicago in 1937 by Lászlo Moholy-Nagy, the New Bauhaus aimed to train “the perfect designer” through a modernist and multi- disciplinary curriculum that encouraged experimentation and broke down the hierarchy between fine and applied arts. At a time when few art schools existed and photography was seldom taught as anything other than a trade, the photography department at the ID was at the forefront of innovative methods of art education.

The ID, located in Chicago at what is now the Illinois Institute of Technology, prepared students to work in the industry with a foundation of strong technical skills while also encouraging them to develop their own voice and style as they experimented with a wide range of techniques and materials.

As scholar Lloyd C. Engelbrecht writes, “Photography throughout the country was effectively revolutionized by what happened under Moholy: first, photography was taught as a basic understanding of light and the manipulation of light; second, it was recognized as central to modern vision, a fundamental part of what Moholy believed it meant to say that someone was literate; third, photography was integrated into a complete art and design curriculum; and fourth, it was taught experimentally, not rigidly or dogmatically or commercially.”1

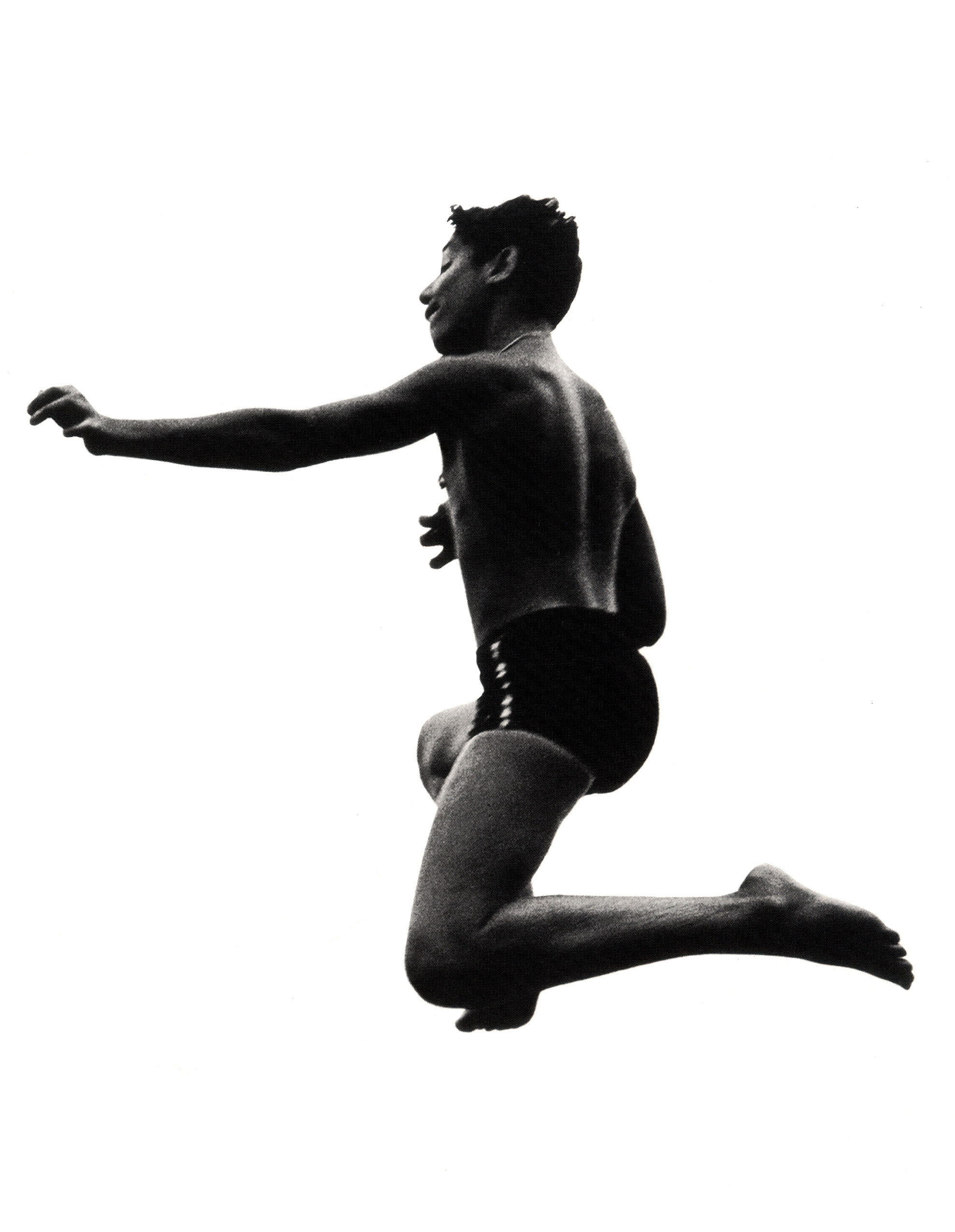

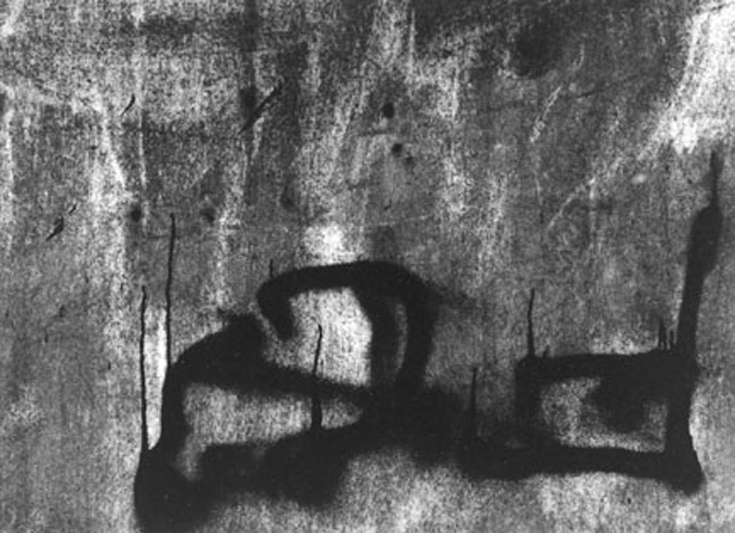

In the tradition started by Moholy-Nagy, the program began with a strong emphasis on observing, using, and modulating light. All students made photograms to observe and record patterns of light and shadow and learn about the light-sensitive properties of photographic materials. Many assignments were formal and technical, while others encouraged students to be aware of social and political issues on the streets of Chicago where they often worked.

Students explored informal portraiture made spontaneously on the street, and self-documentation–the description of oneself through one’s environment. Once they had mastered the basics of the Foundations Course, students were pushed to pursue unique personal projects in which they used photography to see familiar things in new ways. Students of Siskind and Callahan became important artists and influential teachers of the next generations of artists as more and more college level art programs were established following World War II.

1 Lloyd C. Engelbrecht, “Educating the Eye: Photography and the Founding Generation at the Institute of Design, 1937-1946,” in Taken by Design: Photographs from the Institute of Design, 1937-1971, ed.

David Travis and Elizabeth Siegel (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2002), 17.

Select Photographers of the New Bauhaus

Aaron Siskind (United States, 1903-1991) began working in abstract and metaphoric photography In the early 1940s, inspired by his friendships with Abstract Expressionist painters such as Franz Kline and Mark Rothko. On the invitation of Harry Callahan, Siskind joined the faculty of the ID in 1951, taking over as head of the photography program when Callahan left in 1961.

During the 1950s, Siskind’s primary subjects were urban facades, graffiti, isolated figures, and the stone walls of Martha’s Vineyard. Graphic in form, the subjects of each of these series resemble script, reflecting Siskind’s interest in musical scores and poetry. Architecture was on of Aaron Siskind’s principle photographic concerns during the 1950s. For instance, from 1952-1953, he and his students were engaged in an ambitious documentation of the Adler and Sullivan buildings in Chicago. Siskind and Callahan, famous for their synergy as professors and photographers, were reunited beginning in 1971 when Siskind left the ID to join Callahan at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Born in San Francisco in 1921, Yasuhiro Ishimoto (Japanese-American, 1921-2012) grew up in Kochi, Japan from the age of three until he moved to Chicago in 1939 to study architecture. During World War II, he was detained in the Amachi Japanese Internment Camp in Colorado from 1942 to 1944. In 1948, after encountering Moholy- Nagy’s book, Vision in Motion, Ishimoto enrolled at the Institute of Design, and studied photography under Harry Callahan.

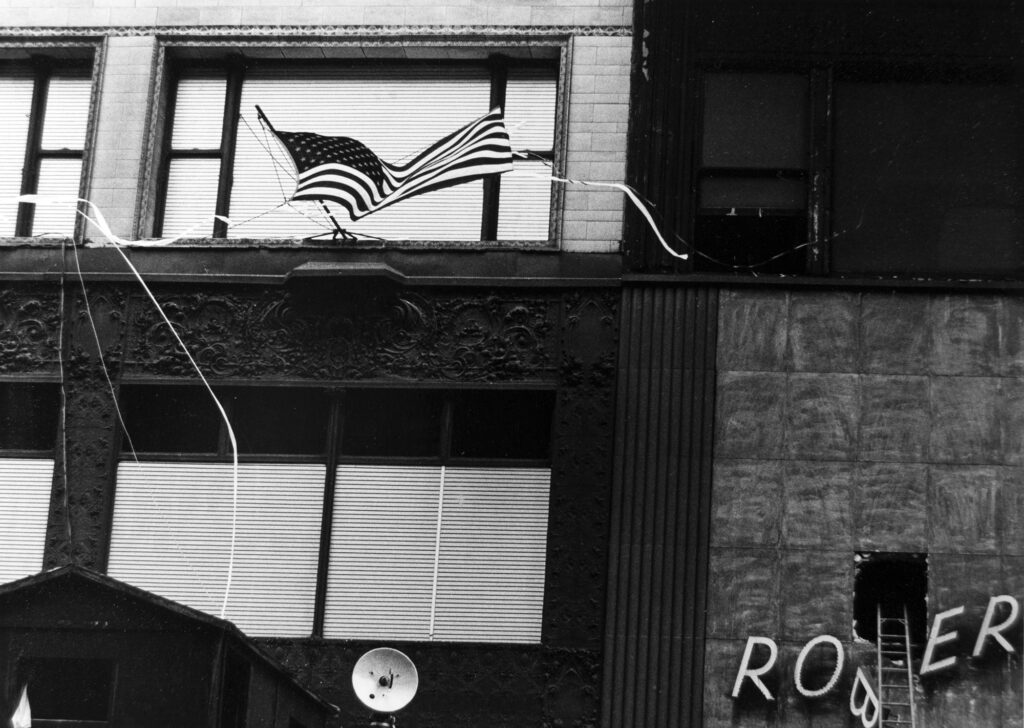

While at the ID, Ishimoto photographed extensively on the streets of Chicago, often documenting scenes that showed the inequality and tension between Black and white residents in a very segregated city. Though Ishimoto returned to Japan in 1953, he again photographed in Chicago from 1959 to 1961 on a fellowship, culminating in two books of photographs called Chicago, Chicago. Moving through Chicago as both citizen and visitor, Ishimoto created documents that speak eloquently of the culture of the city in this time. His photographs present highly original visual spaces, which nonetheless suggest the politics, tensions, and mood of the city.

Activity: Observing Light and Shadow

The word “photography” comes from a Greek phrase that means “drawing with light.” Observing, understanding, and effectively using existing light are essential steps in learning photography and was at the core of the New Bauhaus curriculum. Nathan Lerner (United States, 1913-1997) joined the first class of the New Bauhaus in 1937. There, he invented the “light box,” a modified construction that he used to modulate and photograph the effect of light on objects.

Over the next few days, pay close attention to the light in different environments and at different times of day. Examine how light affects the shape and appearance of people and objects and the mood or feeling of a particular place.

Observe and photograph light and shadow on the street, in your home, and community. Photograph in different lighting situations, at various times of day, and use the light that is available in the environment in which you are shooting.

Try placing your subject in the light or dark areas of the scene. Photograph someone or something placed in light coming through a window. Photograph interesting shadows. Shoot most of your images outside but take at least a few pictures indoors. Try exposing the photo to the shadow areas vs. exposing for the areas in the light. How are the images different? You may not use a flash for any part of this assignment. Print or project a selection of your images and share and discuss them with your peers. What ideas and moods do your images express? How did experimenting with the various lighting situations change your perception of the scene and what it could convey?

Select Photographers of the New Bauhaus

Ray Metzker, Chicago, 1959

Ray Metzker (United States, 1931-2014) questioned the nature of images and the concept of photographic truth. Through cropping, multiple imagery, and other formal inventions, his work explores options for transforming images. “When you look at the multiples, you are aware of patterning and so forth,” he says, “but there is still identifiable subject matter; frequently there are people there; there is a rhythm to those people.” For his 1959 thesis project, My Camera and I in the Loop, Metzker took downtown Chicago as his subject, but renders it in experiments that tell more about photography than they do about the city.

Richard Nickel (United States, 1928-1972) completed a BA at the Institute of Design in 1954 and an MFA in 1957. By the mid-twentieth century, urban regeneration and development in the United States spurred the demolition of historic buildings. Facing this impending loss, Nickel began campaigning for the preservation of American architecture. Starting in the 1950s, he lobbied for the protection of historic structures, researched and recorded their designs, and even personally salvaged some of their ornamental remains. His photographs constitute their own mode of preservation in safeguarding the visual memory of the buildings.

Among this period’s innovators, Louis Sullivan emerged as a father figure whose buildings became Nickel’s primary pursuit. With the help of Aaron Siskind, Nickel sought to create a photographic catalogue of all the works by the firm Adler & Sullivan. Nickel’s final photograph was taken in his attempt to save the Chicago Stock Exchange designed by Adler and Sullivan. He was able to save a large portion of the building’s ornament and the interior of the Trading Room which is now reconstructed in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Activity: Exploring Vantage Point

A vantage point is where the photographer stands in relation to his or her subject. It is a simple and important technique used by photographers. Look at and take photographs of the same subject from several different vantage points.

Harry Callahan (United States, 1912-1999), who joined the ID in 1945 and became head of the photography department in 1949, worked with a unique vantage point. Callahan photographed a variety of subjects, including pedestrians, his family members, landscapes, and architectural facades. For each subject, he pulled on techniques such as extreme contrast, close cropping, and other forms of abstraction. Yet, his goal was to describe, not to conceal or distort. He is best known for his carefully composed studies of his wife, Eleanor.

Inspired by Callahan, photograph your subject at close range, from far away, above, below, the side, and from behind. Look carefully at the images you have created. How does the appearance of the subject change as your vantage point changes? Which photograph do you like the best? Why?

Activity: Create an Image Within an Image

Kenneth Josephson (United States, b. 1932) entered the graduate program at the Institute of Design in 1958. His graduate thesis, “Exploration of the Multiple Image,” implemented in-camera multiple exposures. Josephson is considered one of the early conceptual photographers; he staged simple interventions in the scenes he photographed, including the use of photographs within photographs, and highlighted real but fleeting phenomena that challenge and fool the viewer.

With Josephson’s work as inspiration, make a photograph using an image within an image. You can also use family archives or historical images to superimpose or overlay onto your image. Will you or someone else hold out the image? Will you tape or adhere your selected image onto your background?

Reflect on your chosen background and image you want to superimpose. How are they related or are they opposites or contradictory? How does that relationship between image and background help convey your message or vision as an artist and image maker?

Activity: People Picture Assignment

Barbara Crane (United States, 1928-2019) earned her master’s degree from the Institute of Design in 1966. Crane experimented with creating multiple images of the same subject and then gridding them into one composition. In “People of the North Portal” (1970-71), she photographed people exiting Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, recording a wide variety of expressions and reactions. Some full-body shots, others focusing simply on the faces of her subjects, the photographs depict a large spectrum of human experience.

Inspired by Barbara Crane, make several pictures using one or two of the prompts listed below.

- People close-up, as close as the camera will allow or closer.

- People centered in the picture space.

- People at the sides or edges of the frame.

- People close and far in the same picture.

- People packing the frame.

- Tiny figures in large space.

- Parts of people’s bodies.

- People pictures taken by NOT looking through the camera’s view-finder.

Share and critique the images you make with your peers.