Robert Frank and the Street Tradition

This guide offers a look into photographer Robert Frank’s body of work, The Americans, that was created between 1955 and 1957. Using a small hand-held 35mm camera, Frank edited the over 20,000 frames made during his travels across the United States into a painstakingly edited sequence of 83 black-and-white images. Frank photographed American post-war culture in everyday locations such as pool halls, diners, and on the street. This guide examines the series, as well as Frank’s perspective as an immigrant and the cultural climate in the United States at that time.

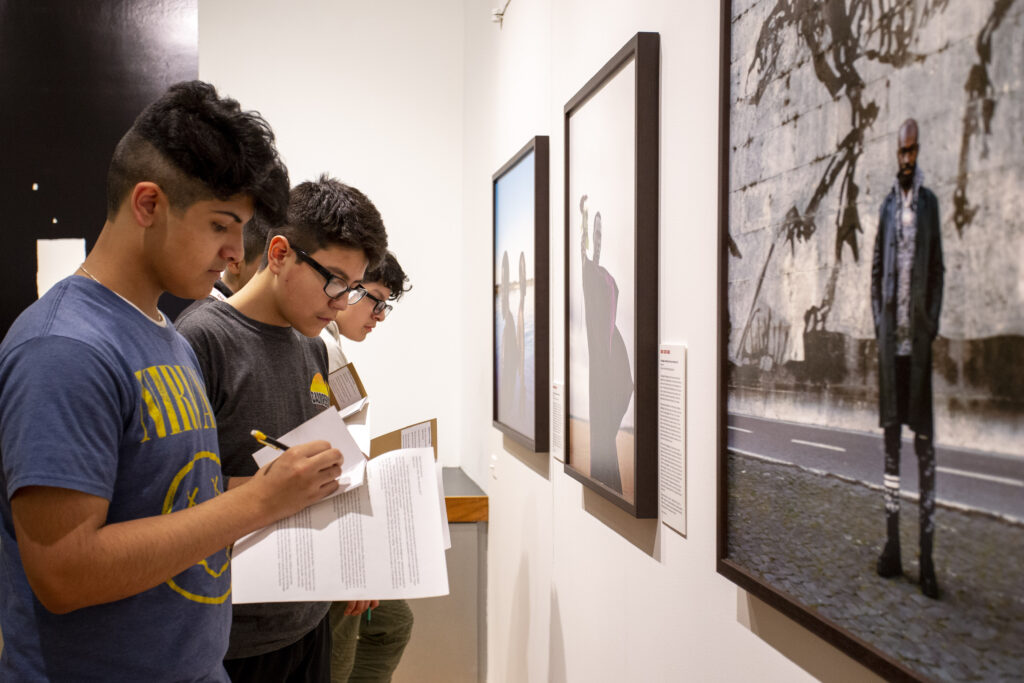

This resource integrates the study of photographs from the collection of the MoCP into secondary and post-secondary fine arts, language arts, and social science curriculum. This guide contains questions for looking and discussion, historical information, and classroom activities and is aligned with Illinois Learning Standards. A downloadable PDF version can be found here.

The museum is generously supported by Columbia College Chicago, the MoCP Advisory Committee, individuals, private and corporate foundations, and government agencies. Special funding for this guide was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Introduction

That crazy feeling in American when the sun is hot on the streets and the music comes out from a jukebox or from a nearby funeral, that’s what Robert Frank has captured in tremendous photographs taken as he traveled on the road around practically all forty-eight states in an old used car…Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world. To Robert Frank I now give this message: You got eyes.

–Jack Kerouac, (from the introduction of Robert Frank’s book The Americans

The Guggenheim Fellowship

In 1954 Robert Frank applied for a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship. In his application he wrote:

The photographing of America is a large order — read at all literally, the phrase would be an absurdity. What I have in mind, then, is observation and record of what one naturalized American finds to see in the United States that signifies the kind of civilization born here and spreading elsewhere. Incidentally, it is fair to assume that when an observant American travels abroad his eye will see freshly; and that the reverse may be true when a European eye looks at the United States. I speak of the things that are there, anywhere and everywhere — easily found, not easily selected and interpreted. A small catalog comes to the mind’s eye: a town at night, a parking lot, a supermarket, a highway, the man who owns three cars and the man who owns none, the farmer and his children, a new house and a warped clapboard house, the dictation of taste, the dream of grandeur, advertising, neon lights, the faces of the leaders and the faces of the followers, gas tanks and post offices and backyards.

In 1955, Frank received his Guggenheim fellowship and $3,600 funding for the express purpose of traveling and photographing around the United States. In 1958, his images became the book, The Americans, first published in France and in United States the following year. This became his most famous body of work.

Cultural Context: the United States during the 1950’s

People in the United States in the 1950s were recovering from a series of extremely challenging events in the preceding decades. Although it is impossible to briefly cover the complicated global atmosphere of post-World War I and II, some key factors that shaped Robert Frank’s The Americans are outlined below.

Americans who fought in World War II were children of those who fought in World War I, which included the first use of chemical and mechanical weapons, gas, and tanks. These same families also lived through the lethal global flu pandemic of 1918 and the Great Depression from 1929-1939. With the U.S. deployment of the atomic bomb on Japan in 1945 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, people were desperate for relief from the years of war, fear, and deprivation. Since many were hungry for security and stability, the popular culture and media of the 1950s placed an emphasis on domesticity, comfort, and economic prosperity. These attributes were reflected in television shows such as the Donna Reed Show and Leave it to Beaver, both of which depicted nuclear families, reinforcing patriarchal cultural norms.

Racial Tensions in the U.S.

During this same time, the U.S. was home to rising racial tensions. In 1954, the Supreme Court decision, Brown vs the Board of Education, declared “separate but equal” schools for Black and white students unconstitutional, and efforts began to desegregate schools and communities. This process was glacially slow after decades of restrictive laws and housing policies had kept Black and white families apart.

Also taking place in 1955, the year Frank created his images, Rosa Parks was arrested in Montgomery Alabama for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger. This event sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott and successfully desegregated Montgomery’s transportation system. Many Black Americans marched and demonstrated in protest during these and other milestones of the 1950s civil rights movement. These activities often sparked violent backlash from white segregationists.

While popular culture presented a cheery facade, others were initiating radical challenges in writing, music, and the visual arts. Robert Frank was one of the artists to document and reflect the sea changes.

Robert Frank, Trolley — New Orleans, 1955; not in the MoCP collection; © Andrea Frank Foundation

A Radical Vision

Robert Frank discovered a more complex story beyond the media dream of America as he traveled and photographed. Most photographs made about the United States in this era celebrated American ideals. Frank’s edgy and honest works challenged aesthetics of the time images, as his Americans often appear bored or alienated and divisions of race, class, and power are evident.

The everyday settings Frank photographed in places, such as bars and along the side of the road, also struck many as not worthy of photographing. Most critics of the time considered The Americans an indictment of American culture made by an outsider and found Frank’s “street” or snapshot aesthetic sloppy. Frank embraced the gritty, grainy quality of 35mm photography and that it allowed him to photograph quickly, often without being noticed.

Frank tapped into currents of dissent and rebellion in 1950s counter-culture. Other artists of the era working in a variety of media also created works that challenged cultural and aesthetic expectations. Jazz musicians including Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie developed BeBop, a style marked by experimentation and improvisation. In 1956, Elvis appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show drawing record audiences. His hip-shaking, rock- and-roll dance moves shocked viewers and challenged conservative attitudes toward sex.

Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac rejected the materialism of the 1950s and celebrated non-conformity and spontaneous creativity in their lives and work. The Beats felt an affinity with Frank’s outsider and radical perspective. Frank’s photographs echoed some of the themes that Kerouac wrote about in his 1957 book On the Road and the two men became friends. In his characteristic stream of consciousness style, Kerouac wrote the introduction to the 1959 American publication of The Americans.

While often critically panned at the time, today Frank’s The Americans is considered a milestone in the history of photography and a seminal and influential example of street photography.

Questions for Looking and Discussion

Look at one frame from The Americans and consider the following questions:

• What is this picture about? Why do you think that?

• What is the mood of the image? How is the mood conveyed through factors such as framing and composition, time of day and use of light, and timing?

• What might be happening beyond the edges of the frame?

• What is the relationship between the elements that you see? How do they work together or conflict?

Now, look at more images and how they are sequenced together. Consider these questions:

• Do the images appear as if they were made by the same person? How would you describe Frank’s aesthetic style?

• What symbols or icons does he use and repeat throughout the series?

• What types of people do you see? How are they similar or different from one another?

Activity: Photographing in the Moment

Street photographers like Robert Frank are very observant of their surroundings and use their cameras to compose and quickly make photographs revealing fleeting occurrences that others might not notice. Go for a walk with your camera and use all of your senses to tune into what is happening around you.

• What do you notice?

• What is interesting to look at longer?

• How could you make a visually compelling picture of that thing or event?

• What vantage point might you use?

• What will you include or leave out of the frame?

While Robert Frank made The Americans images spontaneously, he sought to photograph places and situations that reflected his interests and concerns, many of which were shared by others in the 1950s counter-culture. His project can be viewed as a document that captures the mood of a specific generation and moment in history.

• What social, cultural, or political issues and ideas are of interest to you at this moment in time?

Using the same instructions in the walking activity, seek out scenes and situations that might illustrate your concerns and interests, as well as those of your peers.

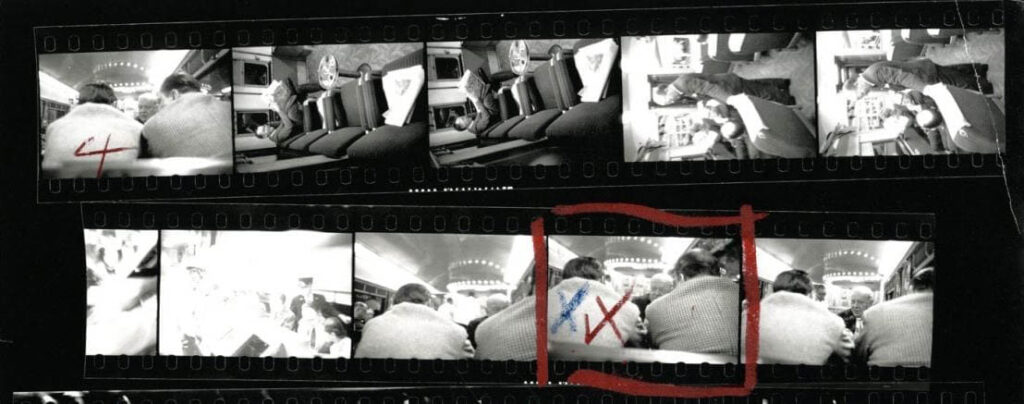

Editing

Frank made 20,000 photographs but edited them down to the frames he felt were the strongest visually and that best illustrated his ideas. He masterfully sequences his images in the book in an order that created visual and conceptual relationships among the images and helped the movement of his loose narrative.

Considering this, try editing your images. Which ones did you select of leave out? Why? Would you like your images to be viewed in a book, exhibited on a wall, or in a slideshow? Do you have any other ideas for how you might like to present your images?

Organize your photographs into the type of presentation and sequence that you think suits them best. Share them with your peers and get feedback on your work.

Activity: Stream of Consciousness Writing

Jack Kerouac’s fluid, loose, and informal style of writing is known as “stream of consciousness,” or what he referred to as “Spontaneous Prose.” This narrative mode presents the thoughts of a person or character as they occur, as if we could see the flow of the writer’s thoughts, feelings, and impressions. You can read an excerpt of his most well-known book, On the Road, here.

Select a photograph by Robert Frank or another photographer. Write about the scene or situation in the picture from the point of view of someone within the image. Consider who this person might be, and what their voice might sound like. Instead of constructing a cohesive narrative, write about the character through free association in the style of Jack Kerouac. What might they see, smell, hear, or feel in this scene? Do not stop to edit–just see what you intuitively create.

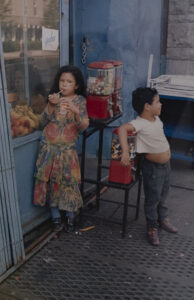

The Street Photography Tradition

Like the spontaneity that Kerouac demonstrates, photographers working in this genre quickly capture candid moments in public places with small hand-held cameras. Many street photographers develop a body of work over time that expresses their subjective point of view of a subject and a distinctive visual style. Technological improvements in film and 35 millimeter camera technology in the early 20th century aided in the development of street photography, allowing photographers to hand hold their cameras and work with existing light shooting multiple frames quickly, without being noticed. MoCP collection artists working in this tradition can be seen below.