An-My Le: Small Wars

About the Exhibition

Under the Clouds of War

This exhibition comprises two photographic series by An-My Lê that explore the military conflicts that have framed the last half-century of American history: the war in Vietnam and the current war in Iraq and Afghanistan. The artist approaches these events obliquely. Instead of addressing her subject by creating reportage images of actual shocking events, she photographs places where war is psychologically anticipated, processed, and relived. Her series Small Wars (1999-2002) depicts men who spend their weekends reenacting battles from the Vietnam War in the forests of Virginia. Lê’s current series, 29 Palms (2003-present), documents a military base of the same name; located in the California desert, it is where soldiers train before being deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. These dramatizations of war (one a reenactment, one a rehearsal) allow her to create a unique kind of war imagery—one that is unexpected, removed, and revelatory.

Lê, who was born in Vietnam in 1960 and came to the United States as a refugee in 1975, created Small Wars to explore, as she describes it, “the Vietnam of the mind.” Although she has vivid memories of the conflict’s waning days from her teenage years in Saigon, she also knows the war, like many of us, through a variety of sources including history textbooks, movies (_Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket_, and so on.), magazines, travel, museum exhibitions, newspapers, and perhaps the experiences of relatives or friends. By joining and documenting Vietnam War reenactors, she explores the cumulative effect that various accounts of war have on memory, both individual and collective, and ultimately questions how we remember, glorify, and imagine war after the fact.

The war games Lê photographed are elaborate. While her pictures present men—some of them veterans, others history buffs—as they simulate combat and war routines using detailed props such as grounded airplanes, tents, and uniforms, the images do not include any of the glaring anachronisms that may have been present. It is the landscape that provides the most telltale signs of falsehood: the flora is typical North American pine and oak forest, nothing like the dense, tropical jungle that covers much of Vietnam. Lê was often asked to participate in the reenactments, her ethnicity presumably adding an element of authenticity to the make-believe. Over the course of the project she acted various roles ranging from that of a translator to, disconcertingly, a member of the Viet Cong. On occasion she included herself in her photographs, as she performed for the male audience that became, in actuality, her real subject. Sensitive to the fact that what motivates such men is often a complex web of psychological need, fantasy, and a passion for history, Lê did not make a mockery of their actions. In fact, some of her most heavily theatrical images she produced were the ones that she considered the least successful and ultimately edited out of the series. This strategy of avoiding parody allows viewers to form their own opinions of the events and, hopefully, to remember the gravity at their root.

By extension, the ambiguity of Lê’s work raises questions about the reliability of seemingly objective historical accounts such as news reports and photographs, which greatly influence how war is communicated and remembered. Lê’s use of a large format camera hark back to early war photography when practitioners such as Mathew Brady, Timothy O’Sullivan and Alexander Gardner worked in the American South recording the Civil War. At that time, due to long exposure times and complicated developing processes, cameras weren’t capable of capturing the chaos and movement of battle, so many of the first photographic representations of war were staid images of its aftereffects. The Civil War photographers were, like Lê, interested in achieving a high level of clarity and craftsmanship in their photographs in order to heighten the sense of direct reportage. Significantly, although Brady and his colleagues depicted the real consequences and casualties of the war, they arranged many of their scenes for dramatic and aesthetic effect. Thus, their works mark the beginning of a long history of war imagery that blends reality and artifice.

With the development of fast films and handheld 35 millimeter cameras at the turn of the twentieth century, the mayhem of the front lines could suddenly be recorded and quickly disseminated worldwide. The era of war photography as we know it, with grisly images from the epicenter of the conflict delivered into our homes on a daily basis, had begun. Famously as first televised war, Vietnam was projected into American living rooms on a nightly basis in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and magazines and newspapers devoted page after page to graphic, bloody pictures of battles, massacres, and life at the front. These images played a key role in the discourse of opposition to the war, and some of them are by now so iconic that they will be forever implanted in our minds.

In contrast, the current war in Iraq is in many ways unseen. There are relatively few photographers embedded in Iraq—Lê tried to be but was denied permission—and much of the imagery that is released by the media is censored and sanitized by government controls and editors’ concerns over appearing to have an antiwar bias. There have been almost no pictures of dead or wounded American service people printed in U.S. publications since the start of the war, even though more than 2,100 American lives have been lost. Instead, the images we have seen have been typically scripted and dramatic: a grubby, disheveled Saddam Hussein immediately following his capture, or George W. Bush’s 2003 photo op on an aircraft carrier, posing in front of a banner reading “Mission Accomplished.” The liabilities of unregulated image circulation were unexpectedly brought to a head with the dispersion of the Abu Ghraib pictures in 2004. Interestingly, one of President Bush’s first reactions to the abuse was to say that he “did not appreciate what he saw,” a statement that subtly equates the images with the actions themselves. Adding to the confusion of information, the entertainment industry is already disseminating pop-culture versions of the war with television programs such as Over There and movies like Jarhead.

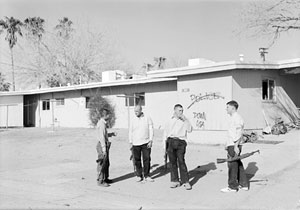

Lê’s pictures from 29 Palms in many ways subversively mirror the media’s sanitized view of the Iraq war. They present no blood, no gore, no cruelty, no shock; they simply show us preparations for battle. Like the forests of Virginia and the Studios of Hollywood (just 150 miles away), 29 Palms is a place where fictions are performed. On the base, marines both rehearse their own roles and play the parts of their adversaries: they are occasionally asked to dress up and act as Iraqi police and civilians, and linguists wearing traditional Iraqi clothing are sometimes brought in to create a ruckus in Arabic. The military housing is tagged with mock anti-American graffiti and fake villages are built of particleboard, their facades like the sets of old western movies. Lê feels that the presence of her camera also feeds the artifice—quite often she thinks it inspires the men to pose themselves to resemble what a “Marine” looks like. She has even heard the soldiers quoting scenes from war movies to one another during training. As Susan Sontag wrote in her 2002 New Yorker essay “Looking at War,” war photographs seem inauthentic if they look too much like a movie still. In a postmodern twist, by taking a documentary approach to the rehearsal for war, Lê asks us to question the very premise of “authentic” photography to begin with.

In 29 Palms, Lê demonstrates a fierce dedication to craft, creating compositions that emphasize the landscape in which the theater occurs. Like the U.S. Geological Survey photographs of the 1870s, or Ansel Adams’s work from the 1930s and 1940s, her images present the American West in lush detail, as epic and imposing. By stepping back and capturing the sublime vistas of the landscape, she shifts some of our focus to the relative insignificance of man. Mountains and desert dominate the series, their vastness making the war elements appear small and toylike, adding to the artificial nature of the scene. Soldiers almost disappear into the landscape, and Lê rarely shows us their faces or provides hints of their emotional state or disposition. This distance invites reflection, and enhances the complexity of her work.

Lê’s pictures have the hallmarks of a documentary project: they are presented in a series, depend on a verbal or written narrative, and require the photographer to seem immersed and “really there”; but they are also obtuse. Traditionally, documentary photography operates on the assumptions of commonly held values and a certain artistic neutrality. Lê’s pictures are most interesting in their ambiguity, however, and in the fact that they discourage foregone conclusions, questioning how much we can really know from documentary photographs. They do not show us what war does, but they do contribute to our understanding of war in a new and interesting way. By bringing added resonance to the phrase “the theater of war,” Lê asks us to reconsider the fictions that cloud the ways in which war is experienced, remembered, and represented.

An-My Lê was born in Saigon, Vietnam in 1960 and came to the United States in 1975 as a refugee. She holds a BAS (1981) and MS (1985) from Stanford University and an MFA from Yale University School of Art (1993). Recent solo exhibitions of her work include 29 Palms at Murray Guy, New York; Small Wars at PS1/MOMA Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, New York; and Vietnam at Scott Nichols Gallery, San Francisco. She is the recipient of a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship (1997), and her work is held in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; and Sackler Gallery, The Smithsonian, Washington DC.

—Karen Irvine, Curator

Image Gallery