The Edge of Intent

About the Exhibition

Work by:

Liset Castillo

Dionisio González

Andrew Harrison

Tim Long

David Maisel

Simon Menner

Danielle Roney

Christina Seely

Eric Smith

Joel Sternfeld

“In the center of Fedora, that gray stone metropolis, stands a metal building with a crystal globe in every room. Looking into each globe, you see a blue city, the model of a different Fedora. These are forms the city could have taken if, for one reason or another, it had not become what we see today. In every age someone, looking at Fedora as it was, imagined a way of making it the ideal city, but while he constructed his miniature model, Fedora was already no longer the same as before, and what had been until yesterday a possible future became only a toy in a glass globe.”

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

In Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel Invisible Cities, Marco Polo captivates the elderly emperor Kublai Khan with tales of fifty-five cities spread throughout the Khan’s fading empire. The Khan relies on the young Venetian explorer to describe the state of his empire but suspects that Polo may be deceiving him, that his cities may not in fact exist.

…once implemented, these idealistic visions fail to deliver, become mired in stasis, and are ultimately incapable of adapting to changing circumstances.

Similarly utopian aspirations of urban planning become a focal point in the exhibition The Edge of Intent, which considers how, once implemented, these idealistic visions fail to deliver, become mired in stasis, and are ultimately incapable of adapting to changing circumstances. Through photography, video, and mixed media, the works in this exhibition warn us of the hazards of thinking big, while urging us to consider the centrality of dynamism in successful urban design. This exhibition also challenges us to see beyond the physical attributes of a city’s layout, and to consider the effects design has upon its inhabitants, who often subvert it.

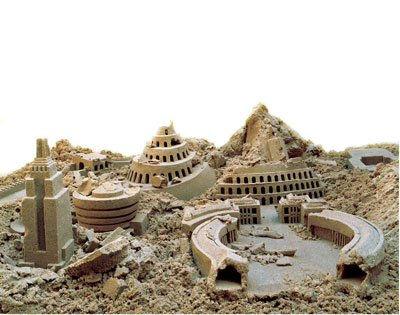

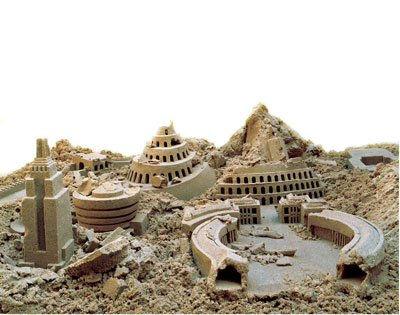

Liset Castillo’s (Cuban, b. 1974) photographs of a fictitious city constructed out of sand could be used for the cover ofInvisible Cities. Through intricate sand castles, Castillo builds a utopian microcosm where different world civilizations converge and ultimately collapse. Playing with architectural monuments such as the Taj Mahal, the Coliseum, the Vatican, the Great Wall of China, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York, Rio’s monumental Christ the Redeemer, and the Empire State Building, her timeless city is both grand and unrealizable. Using projections, drawings, her hands, and a trowel, among other tools, Castillo builds, photographs, destroys, and re-photographs sand sculptures in her backyard Brooklyn studio. The resulting images convey dilapidated cities surrounded by rubble and craggy terrain, implying that history inevitably collapses in on itself.

Moving from sand to animation, Danielle Roney’s (American, 1968) single-channel, three-section video eGoli imagines a fantastical landscape in a mythical “city of gold,” once an alias for Johannesburg, South Africa. During a 2007 residency in South Africa, the Atlanta/Beijing-based artist documented her experience through photographs, video, and sound recordings. Collaborating with animator Jeff Conefry, Roney crafts a hyper-real cyber city and its environs. The result implies a city struggling to find both its own ideal and its desire to become part of a global community. eGoli explores the African countryside and Johannesburg’s environs, and also the molecular structures of the city’s built environment.

Particular notions of an ideal society—“utopia”—often inform an urban plan.

Particular notions of an ideal society—“utopia”—often inform an urban plan. Utopias are places where collective dreams of peace and harmony are realized. But happiness is not necessarily a place. An unobtainable ideal is guaranteed to disappoint. Andrew Harrison’s (American, b. 1970) work explores aspects of urban planning with cartographic experiments that use New Jersey as a potential utopia. He ironically rearranges a road map of the Garden State, his home, based on both mythical qualities and proposed urban plans such as Sir Walter Raleigh’s vision of El Dorado, the biblical Garden of Eden, Plato’s lost city of Atlantis. He also refers to Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, Le Corbusier’s 1935 The Radiant City, and Lucio Costa’s 1957 Pilot Plan for Brasilia. Each newly configured map sources and re-orders the same space—but claims different potential results. This recombination of mythical and ideal narratives onto an alternate place becomes a model for reimagining urban space.

Similarly, Dionisio González (Spanish, b. 1965) pieces together images of the favelas, or shantytowns, of São Paulo, Brazil into long panoramas to which he adds bits and pieces of pristine, contemporary architecture. In part he is reacting to a failed government reurbanization project meant to raise the standards of living for the residents of the favelas. González conceives of his works as proposals for new social centers. Instead of imposing a systematic, orderly structure from an outside urban planner, González reflects the spatial order that already exists in these neighborhoods, one that is chaotic and in flux.

As in González’s study of the favelas, Simon Menner’s (German, b. 1978) project Metacity records the informal structures of the homeless in the cities of Mumbai, Chicago, and Paris. Each of these cities was created from plans that oftentimes reflected the interests of elites, and not the realities of the poor. The port city of Mumbai, ruled by the British East Indian Company as early as 1662, adapted the British colonial model. Napoléon III commissioned Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann between 1852 and 1870 to devise the plan that still defines Paris with its large boulevards and open spaces. Highly influenced by Haussmann’s plan, the renowned Daniel Burnham Plan of Chicago was initially sponsored by the Merchants Club in 1906 and then published by the Commercial Club of Chicago in 1909. Although all three plans endeavored to have a profound impact on a city’s society—and arguably did—they inevitably failed to anticipate evolving urban requirements. For example Daniel Burnham in 1909 did not comprehend how the automobile would transform American cities. And the planners of Mumbai could not have predicted how, after independence in 1947, the population would triple to nearly 14 million. Mumbai has now experienced massive urbanization with little urban planning and currently 60 percent of the population lives in slums. Menner’s photographs question whether there exist common elements in this kind of poverty in different cities around the globe. Menner is not as interested in documenting the homeless existing in the classic slums of third world countries, but in the individual homeless person and how he or she inhabits the modern city.

In another global project looking at the consequences of growing distance from an ideal city plan, Christina Seely’s (American, b. 1976) series Lux, titled after the system for measuring illumination, examines the disconnect between the immense beauty created by human-made light emanating from the earth’s surface and the carbon emissions created by the world’s wealthiest countries—evident as the brightest areas detected on a satellite map. The three regions most visible in NASA images are the United States, Western Europe, and Japan, which together emit approximately 45 percent of the world’s CO2 and, along with China, are the top consumers of electricity and other resources. Seely’s work indirectly explores the realities faced when dealing with the infrastructure of these urban environments and the consequences resulting from their excessive energy requirements.

David Maisel (American, b. 1961), like Seely, is interested in the dialectic balance between what is seen on the surface of a photograph and the complex reality that lies beneath, and how beauty can suggest the ideal while obscuring the often darker side of a subject. In The Lake Project, Maisel’s stunning aerial photographs of the Owens Valley in southeastern California appear otherworldly. In 1913 the City of Los Angeles diverted water from this valley into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, providing a substantial amount of the city’s water supply. By 1926, the water in the valley was essentially depleted, leaving a vast exposed salt flat with unusually condensed mineral levels and extremely vulnerable top soil. With the notorious high winds in the area, the resulting persistent dust cloud has become the largest source of particle matter pollution in the United States. The surreal colors captured by Maisel are both beautiful and fearsome. Serving as a coda to The Lake Project, Maisel’s Oblivion series views Los Angeles devoid of color. He inverts the prints to a negative and implies that we are seeing the organic substructure of the city as in an X-ray. This is a similar strategy used in Danielle Roney’s eGoli, in which she virtually penetrates the molecular structures within her city of gold.

Akin to Maisel’s documentation of what is left behind after infrastructure becomes obsolete, photographer Joel Sternfeld (American, b. 1944) has documented the degraded landscape of Manhattan’s High Line—the abandoned elevated railroad tracks that run between the West Village and 34th Street. Originally built in 1934 to transport goods from the river, the existence of the derelict tracks has caused great debate in a city trying to balance high demand for built property with the need for open space. Its beauty is in part generated by the marks left on it from the fractured social history of its surroundings, the long history of New York City as a point of departure and arrival for goods and people. The current plan is to reuse this infrastructure to create a promenade where one could travel by foot between Penn Station and the Hudson River Pier and from the convention center to the Gansevoort Market Historic District, without crossing a street.

From a kayak and along the shore, Tim Long (American, b. 1951) records the balance between industry and recreation and the transition from urban to rural along the Illinois Waterway to the Mississippi River. Initially flowing east into Lake Michigan, the Chicago River was reversed in 1900 by the Sanitary District of Chicago. Massive amounts of sewage and pollution were poured into the river from homes and industrial sources causing, among other things, a cholera epidemic. While the pollution remains a constant to this day, Long’s photographs document the awkward proximity of leisure and commerce along the waterway.

Eric Smith’s (American, b. 1947) photographs record the Michigan Central Train Station in Detroit, once a vibrant hub of transportation, but now an abandoned, neglected, and graffiti-strewn monument to Detroit’s past. Built in 1913 in the Beaux Arts Style and closed in 1988, the building’s marble walls and Doric columns are solidly intact and the space retains its majestic scale. Smith uses digital techniques to depict the station with a sensuous, intensified luminosity, until the photographs resemble meticulously painted illustrations. On a cursory view these photographs can easily be taken for inventive depictions of a mythical setting, similar to Piranesi’s subterranean prisons. The station conjures Liset Castillo’s deteriorating sand castles, perhaps projecting the fall of both the Roman and the American empires.

Cities can be tenuous places. As Marco Polo describes the city of Thekla to Kublai Khan:

Those who arrive at Thekla can see little of the city, beyond the plank fences, the sackcloth screens, the scaffoldings, the metal armatures, the wooden catwalks hanging from ropes or supported by sawhorses, the ladders, the trestles. If you ask, “Why is Thekla’s construction taking such a long time?” the inhabitants continue hoisting sacks, lowering leaded strings, moving long brushes up and down, as they answer, “So that its destruction cannot begin.” And if asked whether they fear that, once the scaffoldings are removed, the city may begin to crumble and fall to pieces, they add hastily, in a whisper, “Not only the city.”

— Natasha Egan, Associate Director and Curator

Image Gallery