Our Origins

About the Exhibition

Featuring the work of:

Jenny Akerlund

Julia Büttelmann

Alison Carey

Eric William Carroll

Michelle Ceja

Ken Fandell

Jason Lazarus

Aspen Mays

Scott McFarland

Patricia Piccinini

Mark Ruwedel

Jennifer Ray

Alison Ruttan

SEMICONDUCTOR

Rachel Sussman

Penelope Umbrico

Perhaps the relative permanence of the past, established as history, explains our tendency to search for that meaning by looking backward, to our origins.

Human consciousness is finite. Each of us lives for only a passing moment. Perhaps our ephemeral nature compels us to search for the meaning of existence. And perhaps the relative permanence of the past, established as history, explains our tendency to search for that meaning by looking backward, to our origins. Certain points of origin can be accessed: we celebrate birth and document family lineage. But the original occurrences that formed life, and the planets and the cosmos that surround us, remain too distant and abstract for even our sophisticated intelligence or technologies to fully explain.

In their book Human Origins, Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall describe an “almost universal need shown by most civilizations, religions, and philosophical movements of the last five millennia to address the [question of] origin, extending not only to people, but to Earth itself.” (1) Today, many people turn to science in search of accurate descriptions of deep history. Countless scientific endeavors – including investigations into evolution and the Big Bang – have attempted to comprehend stretches of time that extend backward or forward on a scale that is nearly inconceivable in human terms. Those efforts seem intrinsic to understanding our collective heritage and to imagining the future of our species. Yet such endeavors also expose both the material and intellectual boundaries of our knowledge about who we are and how we came to be.

In their efforts to better comprehend great spreads of space and time, scientists often use photography to illuminate evidence that lies beyond the limits of unaided vision. Like science, photography offers arrangements of information, pulled out of the complexity of the world as a whole, and presented with seemingly impartial clarity. Used in combination, science and photography have produced some of the most significant discoveries of the past two centuries, including countless images of outer space, X-ray diffraction scans used to map the structure of DNA, and CAT scans that have provided new insight into the original form of fossilized specimens. In spite of what can be understood through systematic research, rigorous analysis always reveals an absence of information. All of our clues about the events that occurred prior to recorded history are deduced through studies of trace remnants that predate us. Much like photography, which gives only a semblance of reality, human stories of our origins are dotted with unknowns.

The exhibition Our Origins considers the human inclination to trace our beginnings beyond recorded history and explores our limited capacity to draw conclusive answers about the meaning of life. Sixteen participating contemporary artists use photography, video, drawing, and sculpture to reflect on natural history from a distinctly human and often humorous point of view. This approach emphasizes questions about the paradoxical nature of human intelligence in a universe that cannot be altogether explained. Where did we come from? How is it that we have come to possess a consciousness and a psyche? What does the future hold? The exhibition does not provide explicit answers to the great, mysterious questions of our universe, but rather confronts, and then ponders, the very idea that such questions might be unanswerable.

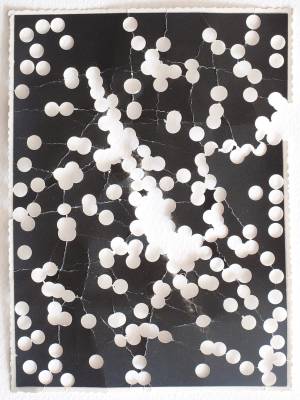

Artist Aspen Mays (American, b. 1980) translates perplexing evidence of our cosmic history into photographic works that ask far larger questions than they attempt to answer. Her photograms of TV static refer to NASA’s claim that 1 percent of television static is caused by cosmic radiation left over from the Big Bang. Seeing remnants of the explosion that created our universe, broadcast over a device that has dominated modern media culture demonstrates the curious ways our ongoing cosmic story is transmitted and made visible through technology. Punched Out Stars is another grouping of images, created when Mays was conducting research on a Fulbright at the European Southern Observatory in Chile. While exploring the facility’s grounds, she discovered an abandoned black-and-white darkroom with old photographs of stars tucked into the room’s hidden corners. Using a hole punch, she removed the stars, leaving behind unmarked areas that might represent gaps in our efforts to map outer space.

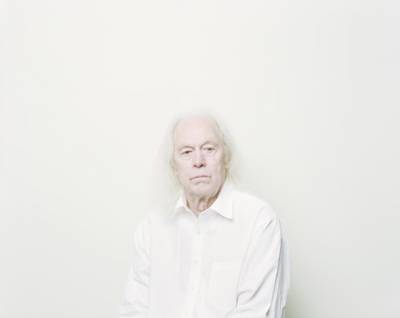

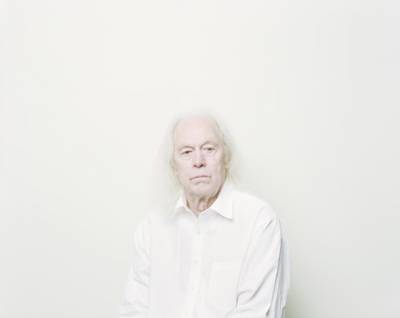

Jason Lazarus (American, b. 1975) also considers the edges of scientific observation with his portrait of astrophysicist Eric Becklin. Becklin is renowned for using infrared technology to image deep space, including the first images of the center of our galaxy. In Lazarus’s portrait, Becklin’s pale complexion nearly dissolves into a white background, suggesting his power to transcend the earthly confines that ordinarily restrict human vision, if only photographically. Jenny Akerlund (Swedish, b. 1984) is comparably interested in a tension between closeness and distance. Her graphite drawings reproduce photocopies of textbooks containing pictures of the moon. The moon was likely formed by a forceful impact that occurred during a gaseous period in the earth’s early existence. Like Akerlund’s works, which oscillate between the intimacy of a hand-rendered drawing and a detached coolness inherent to photocopies, the moon alternately feels like an essential part of earthly existence and a distant unknown.

Satellites of a different sort inform the work of artist team SEMICONDUCTOR (*Ruth Jarman*, British, b. 1973 and Joe Gerhardt, British, b. 1972). The duo created their video Black Rain by cutting together footage taken from NASA cameras that are rotating the sun along the same orbital path as the earth. NASA ordinarily processes captured imagery before distributing it to the public, but here it is shown raw, with numerous digital artifacts. Installed in a gallery, the video produces a sensation nearing the sublime, with occasional interruptions of digital noise that remind us of the ways technology mediates our experience of outer space.

Astronomy is always an exercise in history, because our universe is billions of light years large. Closer to home, there are many terrestrial artifacts that offer different forms of insight into deep history, while also inspiring artists. The ancient marine environments in the photographed dioramas made by Alison Carey (American, b. 1966) re-create scenes from the earth’s Paleozoic Era with incredibly rich detail. Printed with liquid emulsion on black glass, these images look simultaneously alive with lush realism and quietly preserved as fossilized remains. The sensation of looking at each work’s surface gives one the feeling of quietly floating in a breathtaking, liquid past. With his photographs of fossilized dinosaur tracks that are embedded in the American landscape, Mark Ruwedel (American, b. 1954) takes a more straightforward approach to depicting scenes of history. He records massive divots in the earth’s surface that were made by creatures who traversed the land millions of years ago, yet each picture has a mysterious connection to today that evokes the weight and movement of a living animal that has only just passed by. Paired with pictures of early human footpaths, the images ominously suggest visible parallels between our own walking patterns and those of previously dominant species that are now extinct. Throughout Ruwedel’s works, layers of history that are written onto the land coalesce, to show ways animal and human imprints have formed the earths surface alongside dramatic geological transformations. Rachel Sussman (American, b. 1975) travels the world in search of connections with the ancient past, but finds access points in living plants rather than fossilized remnants. Her photographs of organisms that have been alive for thousands of years catalog longevity on a scale that is awe-inspiring and nearly unbelievable. The oldest living organism that she has encountered is Siberian Actinobacteria, which has been alive for 400,000 to 600,000 consecutive years. Experts generally estimate that modern humans first appeared on earth around 500,000 years ago, meaning that these bacteria may have originated even before our species.

Looking still deeper into natural history, we see that many of the works included inOur Origins address evolution, particularly the ways it has produced distinct behaviors in various life forms. Often the study of evolution seeks to determine the characteristics that distinguish humans from all other organisms, as is the case withAlison Ruttan (American, b. 1954). While spending time at Wild Animal Park in San Diego, Ruttan noticed what zookeepers at the facility have long known bonobo apes pluck and groom their hair to cultivate individual hairstyles. Intrigued, she began taking portraits of the bonobos, later reducing the color palette of the pictures and drawing over the head and facial hair of each subject with pen ink. By accenting an uncanny similarity between the bonobos’ grooming habits and our own, Ruttan’s works playfully articulate the likelihood of a common ancestor. Another series, The Four Year War at Gombe, illuminates additional behavioral links between us and other primates. The pictures depict people acting out scientist Jane Goodall’s accounts of a Tanzanian chimpanzee community that she observed for many years in the 1960s and ’70s. After living in peaceful cohabitation, the chimp group inexplicably broke into two, with one faction waging a long-term, calculated war on the other. Goodall was the first scientist to observe animals engaging in long-range planning and strategic thinking. In scenes of both peaceful, bucolic existence and blood-drenched massacre, Ruttan’s pictures of people behaving like apes reveal a blurred distinction between animal and human, showing our behavior to be more animalistic than is often imagined. Sexual behavior motivates the scenes in Jennifer Ray’s (American, b. 1984) photographs. She visits parks where men meet to have anonymous sex and finds evidence of their encounters within a lush natural landscape. Plants often appear to be entwined with one another or at seed, suggesting that sexual reproduction is nearly universal among organic life forms, but love is not. The biological draw to copulate is a fundamental cornerstone of human existence, yet here we can see its complexity. Patricia Piccinini (Australian, b. Sierra Leone, 1965) further complicates biological impulses by considering our urges to mate and parent children. Science Story is a grouping of four fictional tableaux set in the laboratory of a male and female scientist. The team’s research has yielded a giant, genetically engineered pet mole that has been designed to provide humans with a living creature to nurture. The nearly hairless animal appears in an incubator and also cradled in the arms of both scientists, looking as much like an infant in a hospital delivery room as a scientific experiment. Both scientists seem lost in an unrequited fantasy, projecting instinctual desires to couple and form a family onto their mole specimen. In compelling fashion, Piccinini considers the ways our interests in lust, love, and family are often interrelated, while also addressing the increasingly common practice of engineering organic life to curb physical and psychological desires embedded within our nature, often with compromised results.

Considering human behavior from a different angle, Penelope Umbrico (American, b. 1957) examines a relationship between intuition and photography with 7,626,056 Suns From Flickr (Partial) 9/10/10. The work presents numerous pictures of the sun that Umbrico found on the image-sharing website Flickr, by keying in “sunset” – not surprisingly, one of Flickr’s most popular search terms. Evidently a great number of humans photograph our closest blazing star. Perhaps this urge to capture the sun is due in part to convention, but an instinctual attraction could also be the motivation. With our deepest sensibilities, we are aware that life on earth thrives due to our unique proximity to the sun; its appearance seduces us even in the cool realm of cyberspace. Michelle Ceja (American, b. 1988) also turns to the Internet in search of answers with her triptych Apocalypse: a set of altered images yielded by the Google search “What will the end of the world look like?” The two outer panels of the triptych each show a cosmic image compressed into a small strip of visual information, with a center panel depicting a glowing, planet like pink circle. A tension between two and three dimensions suggests that space and time may be folding into one another, a common theme in both physics and science fiction. This collapse can also be seen as a metaphor for the Internet, which compresses great amounts of information and distance into a virtual space. The work refers to a common fantasy in popular culture. Be it time’s beginning or its end, we yearn to see moments of massive cosmic change. Perhaps, Ceja suggests, our virtual technology is the medium through which such change will be experienced.

Photographic information obtained by one of the most high-tech scientific devises in use today prompted Ken Fandell (American, b. 1971) to create his video The Most Important Picture Ever. In 2003, the Hubble Space Telescope made a ten-day exposure of hundreds of galaxies, registering light that is more than ten billion years old. Fandell appropriated the image and used an animation technique called “shape tweening” to slowly condense the visible galaxies into a bite-sized Cheeto on a hardwood floor. As the video moves from the colossal to the trivial, a sense of disoriented reverie develops, where the universe seems to be both expanding and contracting in infinitely complex ways. Initiated by a Google image search for “the most important picture ever” and a chance encounter with a cheesy snack, the work considers not only the act of stargazing, but also the impulse to search the Internet for visions of what lies beyond the earth’s surface.

The intersection of research and fantasy also becomes fodder for Eric William Carroll (American, b. 1980). His project G.U.T.Feeling is a collection of found scientific documents and self-made photographs that draw on recurring themes and images in theoretical physics. Graphs, charts, drawings, and photographic records are arranged in orderly groupings, playfully traversing fact and fiction to give a pieced together account of the order of the universe. The series as a whole is Carroll’s attempt to create his own Grand Unification Theory (G.U.T.), an idea inspired by efforts in particle physics and string theory to find a single, interconnected explanation of all occurrences within the Universe, past, present and future. In an act of lighthearted contemplation, Carroll exposes the absurdity of trying to comprehend the whole of existence. His title highlights the role of intuition in human cognition and scientific endeavors.

Julia Büttelmann (German, b. 1961) and Scott McFarland (Canadian, b. 1975) both consider the apparatuses of scientific discovery. Büttelmann’s cardboard reproduction of a microscope kit brings to mind a science classroom in an elementary school, where students might observe simple cellular structures firsthand. Though the device seems to promise the possibility of scientific exploration, ultimately, its fake construction prevents any potential for discovery. Also pondering instruments used to observe natural phenomena, McFarland created a photograph showing figures entering the Hampstead Observatory, a more than 100-year-old structure housing a telescope located at the highest point in London. An onsite rainwater collector is also pictured nearby. These antiquated devices are modest in comparison to the highly technological instruments used by cutting edge scientists. Fittingly, this particular observatory is largely used by individuals from the general public who visit with quaint curiosity, rather than scientific aims. Upon close inspection, hints that the image is actually digitally stitched are left visible, exposing the subjective decisions that are inherent to the photographic medium. Photography and science are often viewed as disciplines of objectivity. Here, the tools of each of them are scrutinized, calling into question the neutrality of both and suggesting that even when used with innocent intentions, their effects on perception are profound.

Our faith in the veracity of the photograph as an instrument for scientific observation and the role that faith plays in shaping our sense of the order and origins of the universe are interestingly considered by all of the artists represented in the exhibition. The places where systems of knowledge fail to completely explain the nature of existence often serve as points of departure for these artists. Using speculation and, at times, humor, they illuminate ways we contemplate questions beyond our comprehension, and find meaning not only in what we know, but also in all that remains mysterious.

Allison Grant, Curatorial Assistant

(1) Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall, Human Origins: What Bones and Genomes Tell Us About Ourselves (Nevraumont Publishing Company, 2008), p. 12.

Gallery Talk: Alison Carey. In conjunction with Our Origins at the Museum of Contemporary Photography from MoCP, Columbia College Chicago on Vimeo.

Gallery Talk: Jennifer Ray. In conjunction with Our Origins at the Museum of Contemporary Photography from MoCP, Columbia College Chicago on Vimeo.

Gallery Talk: Ken Fandell. In conjunction with Our Origins at the Museum of Contemporary Photography from MoCP, Columbia College Chicago on Vimeo.

Gallery Talk: Allison Ruttan. In conjunction with Our Origins at the Museum of Contemporary Photography from MoCP, Columbia College Chicago on Vimeo.

Allison Ruttan in Conversation with Laurie Santos, PHD. Moderated by Gabriel Spitzer. In conjunction with “Our Origins.” Part 1. from MoCP, Columbia College Chicago on Vimeo.

Allison Ruttan in Conversation with Laurie Santos, PHD. Moderated by Gabriel Spitzer. In conjunction “Our Origins.” Part 2 from MoCP, Columbia College Chicago on Vimeo.

Image Gallery