Shirana Shahbazi: Goftare Nik / Good Words

About the Exhibition

In her project Goftare Nik/Good Words, Shirana Shahbazi (Iran, Swiss resident, born 1974) reflects on the impact of pictorial representation in the construction of notions of culture, religion, and identity. Taking the city, surroundings, and people of Tehran as her subject, Shahbazi explores trans-cultural attitudes and habits existing in present-day Iran and where they collide—and blend—with stereotypes of traditional Islamic culture.

The recent history of Iran familiar to most outsiders begins with the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and is followed by a list of the social restrictions imposed by its leaders. The traditional Islamic dress code of full body covering was imposed upon women, and alcohol, pop music, dancing, and birth control were among the many things banned. Yet this version of history is incomplete and only offers a narrow perception of a culture—which Shahbazi seeks to widen.

Today, almost a quarter-century after the revolution, over fifty percent of Iran’s population is under the age of twenty-five. This new generation, too young to remember the revolution, is quietly pushing the boundaries of what is tolerated by the regime. It is often reported in the press that women wear lipstick and nail polish under their chador, young people gather at underground parties, and the wealthy teenagers go skiing on weekends and e-mail cyber-friends overseas. Iran today is a country carefully negotiating a balance between strict theocratic law, modernizing influences, and increasing demands for reform.

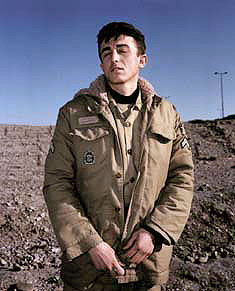

Shahbazi’s site-specific installation of floor-to-ceiling imagery serves as a visual analogue for the complexity of present-day Iran. Images of construction sites and cityscapes crisscrossed by highways and power lines capture the rapid growth and modernization of Tehran. An empty soccer stadium with two portraits of the Ayatollahs Khomeini and Khamenei looming above the stands and hillsides inscribed with praises of military victories depict the omnipresence of the ruling regime. Other photographs demonstrate how local customs co-exist with international popular culture: a family of four enjoying cotton candy in an amusement park; a young woman in a headscarf, khakis, and green tennis shoes smoking a cigarette; a bride in a long white wedding gown striking a clichéd pose. For a Western viewer, many of Shahbazi’s images are perhaps unexpected, such as the concrete buildings of Tehran shrouded by a snowstorm or a young woman dressed for the evening in a slinky party dress. Although sometimes Shahbazi captures a chance moment, many of her photographs are staged-a strategy that undermines the presumed documentary nature of her pictures and belies a simple, straightforward dichotomy of East and West.

Within her installation Shahbazi incorporates painted copies of her photographs made by Iranian billboard painters she has hired for this purpose. One of the most conspicuous visual features of Iran today is the murals and billboards painted in a reductive style that endorse various commercial products or celebrate religious leaders and “martyrs.” By subjecting her vision of ordinary people and scenes to the hyper-real language of billboard advertising, Shahbazi offers an alternate iconography in which she deconstructs official sanctioned or invented myths. Combined with her photographs, these paintings formulate a poignant exploration into the unreliability of cultural representation as they celebrate everyday heroes.

Shahbazi’s title, Goftare Nik/Good Words, comes from the Zoroastrian tenet “good thoughts, good words, good deeds.” Shahbazi feels that the teachings of the ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, practiced by relatively few Iranians today, heavily influence Iranian culture. She chose the title because she was attracted to the promising nature of the tenet. Like these words, Shahbazi’s images are constructed bearers of meaning. In negotiating the unstable terrain of representation, Shahbazi creates an auspicious opportunity to investigate the trappings of our visual and cultural codes.

Image Gallery